In facial plastic surgery, one of the hottest topics is ethnic rhinoplasty. An increasing number of non-Caucasians are approaching physicians with nose job needs. Each ethnic group requires a slightly different approach, says Samieh (Sam) Rizk, MD, FACS, board-certified plastic surgeon in New York City.

“In fact, 30 to 40% of my practice today is focused in the area of ethnic rhinoplasty,” he adds, “and that number continues to grow.”

Rizk is a recognized expert on the latest advances in facial plastic surgery techniques and has written and lectured extensively on current concepts. He is a double board certified facial plastic surgeon and director of Manhattan Facial Plastic Surgery, PLLC, in New York City.

Known for his unique and innovative techniques for natural and beautifully sculpted noses, Rizk was one of first to do the combined endonasal rhinoplasty and sinus/septal surgery procedures (article published in Annals of Plastic Surgery), and is a pioneer of the 3D virtual rhinoplasty surgery, which has dramatically increased precision and decreased recovery time for rhinoplasty surgery patients.

Rizk uses tissue glue instead of conventional packing after rhinoplasty. He feels packing creates more swelling, is painful, and distorts the appearance of the nose. In addition, he has developed techniques of using various tissue sealants as well as shorter scars in order to give patients less recovery times.

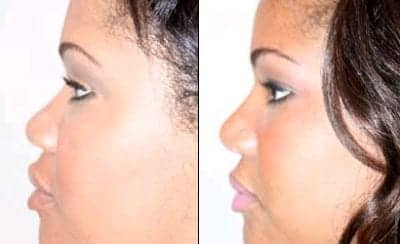

This 26-year-old Middle Eastern patient underwent rhinoplasty to refine her tip and provide tip support. She had a flat tip with thick skin and no tip support due to weak cartilages.

The patient is shown after rhinoplasty with grafting to define and strengthen the nasal tip done through the endonasal approach

According to Rizk, ethnic rhinoplasty is defined in patients with thick skin and weak cartilage. The particular ethnicities where these elements may be found include Asian, Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, African American, and Hispanic/Latino patients.

Why the sudden interest in rhinoplasty from people in these groups?

“They have always been interested, but today they represent a larger percentage of the population, especially in my home city of New York,” Rizk says. “However, I do have patients who come to me from other areas—Philadelphia, Connecticut, New Jersey, and surrounding areas. I’m sure physicians in other large metropolitan hubs, like Los Angeles, are seeing a higher percent of ethnic patients, as well.”

THE DIFFERENCES

The traditional excisional rhinoplasty approach actually makes non-Caucasian patients look worse, Rizk explains. “The techniques used in reduction rhinoplasty in the normal, average Anglo-Saxon patient are fundamentally different from the techniques required in ethnic patients, and generally ineffective,” he says.

“Most ethnic patients want better definition and more of a bridge. Some of those patients will require an implant on the bridge. Those that want more tip definition will require cartilage grafts and special suture techniques to define the tip, as well as select de-fatting in certain areas.”

Rizk has developed his own approach to address the issue for his ethnic and multiethnic patients. For example, his approach to de-fatting will vary depending on the patient’s ethnic group.

“In most ethnic groups, the areas on the side wall and the tip edge where the tip connects to the nostril contain a little extra fat that needs to be removed,” he says. “Some ethnicities have a large fat pad in-between domes that needs to be removed to bring domes closer together. Getting a refined tip is dependent on proper evaluation and correction of the amount of fat in the nose, in addition to specific cartilage techniques to get a well-defined tip.”

One key question that comes up often is, what are the top factors to consider in ethnic rhinoplasty? For example, with regard to tip projection, how does the practitioner address this in ethnic patients? Tip grafts, Rizk says, to provide tip definition.

“The tip graft acts as central pull that pushes into the thick skin and creates definition,” he says. “If a patient has skin that is a centimeter thick, and tip cartilages are weak, then there is nothing that will give that tip definition unless you use a cartilage graft. The cartilage graft acts like the central pole of a tent, standing up and pushing up through the thick skin to give tip structure.

“I also use a special suture technique in lower lateral cartilages. What is called a ‘spanning suture’ can add further tip definition, and then I use an onlay tip graft to give projection. Projection is defined as distance between the nose where it inserts to the upper lip and the front-most forward part of the tip. Most Asians, some African Americans, as well as some Mediterranean patients have decreased projection where the nose is too close to the face—or ‘flat.’ “

The cartilage for the graft comes either from the septum or the ear. “In my experience,” Rizk says, “ear cartilage is not adequately strong to provide good tip support. To get good support, it is better to use septum cartilage or rib cartilage.”

That being said, ear cartilage is excellent when used as an onlay tip graft, he adds. Think of a straight pole with a little umbrella on top. The curved umbrella comes from the ear—that goes on the tip. The thing that holds the umbrella up needs to be straight enough and thick enough so that septal or rib cartilage works better. “Generally, I prefer septal, but for the tip graft I prefer the curvature of auricular cartilage, because it doesn’t have sharp edges and it creates smoother results,” Rizk explains.

LOW DORSUM

How does Rizk accommodate Asians and African Americans, who typically have a low dorsum? In Asia, physicians tend to use silicon implants in rhinoplasty. “I don’t recommend or use silicon implants because they move and never become integrated in the nose,” he says. “They can even become infected.”

The patient is an African American female who underwent open rhinoplasty with alar base reduction.

She is shown preoperatively and 6 months postoperatively (with tip grafting).

When Asian patients come in for revision rhinoplasty, Rizk takes out silicon implants and use banked rib cartilage or Medpor (Porex Surgical Inc, Newman, Ga). “Medpor integrates very well because it has little holes in it,” he says. “I don’t feel the need to harvest the patient’s rib cartilage—it seems too risky to go into a patient’s chest to repair their nose. Not only is it two procedures, but there is a risk of pneumothorax (dropping a lung), and that risk is just not worth it to patients.

“If someone comes to you for primary or revision and they hear you have to go into their chest to get cartilage and there is a significant risk of problems, then that is a real reality check for the patient. The advantages of using a patient’s own rib are ambiguous and unclear. Published literature has documented excellent results with banked rib cartilage. So, my preference for the dorsum in Asian, African American, and some Hispanics is banked rib or Medpor.”

Medpor does not absorb, and that’s a big advantage, Rizk says. “It becomes integrated because it has little holes in it. However, if it becomes infected it is extremely difficult to remove. There are some disadvantages to using banked rib cartilage, as well. It can warp and twist, and it can absorb into the patient’s tissues. Some might consider it to be a less permanent material in rhinoplasty.”

Rizk says he is very selective about who gets Medpor. He does not use Medpor or other implants in diabetics or immunocompromised patients, or patients with thin skin. “Patient selectivity is important to the success of alloplastic implants, and a thick soft tissue envelope is important to the success of Medpor,” he says, adding that he remains open when it comes to the use of Medpor versus rib versus ear/septum grafts, and he uses all these types of implants/grafts as needed on a case-by-case basis.

“It really is ideal for use in thicker-skinned, ethnic patients, because it camouflages so well,” he notes.

What technique has been most successful in narrowing the nasal bridge? “It’s best not to just lay implant on top of wide bone,” he says. “Results are better when you bring bones in very close to [the] face. This procedure is called a low low osteotomy—I’ve achieved excellent results using banked rib cartilage. You actually bring the bones in and then manipulate the implant. Sometimes ethnic bones are short and not wide enough to create a significant difference. If the implant is simply placed on top of the bone, you can sometimes see it lying on top of a wider bridge and there isn’t a continuous line between the implant and the face. The goal is to go very near the face and bring the extra-wide piece in to achieve a natural-looking dorsal narrowing.”

RHINOPLASTY IN ETHNIC MEN

African American men, in particular, sometimes have a high forehead compared to a low bridge. Some require a cartilage graft in the angle between the nose and the forehead, for which Rizk will use crushed cartilage, placing it inside between the nose and the forehead in a small pocket. This technique softens the transitional zone between the forehead and nose and gives a smoother transition, he says.

Nostril reduction is an important consideration in African Americans and Asians. “If nostrils are brought in too much, the part where nostril connects to nose will be very triangular. Picture Janet Jackson. The key is to make a conservative reduction—take a wedge of nostril and don’t just bring it in; rotate it in. This technique doesn’t result in notching, which is how we refer to that triangular appearance.”

When doing a nostril reduction, Rizk adds, if you are in doubt about how much to bring it in, then do just a little. If necessary, a smaller procedure can always be done later to take more.

“Remember, it’s much harder to add than to take away,” he says. “In fact, if you are in doubt about whether to do one in the first place then it’s better to wait. The follow-up procedure can be done after the patient heals under local anesthetic and only takes about 10 to 15 minutes. So, that’s a much better option for the patient than trying to add in more if too much is removed.”

FROM THE MIDDLE EAST

Increasingly, rhinoplasty has become very popular in the Middle East, which means that increasingly surgeons should note the particular differences when performing procedures on that ethnic group.

“Middle Eastern patients tend to have a nasal bump—meaning they don’t have a flat bridge—and a droopy tip,” Rizk says. “They don’t need implants, but they do need dorsal reduction and tip support. This procedure works really well because the cartilage from the dorsum can be used to provide tip support. Sometimes, you can remove the nasal bump and use the curvature of the bump to give more tip definition and projection.”

Cartilage can be obtained from the patient’s own septum, he adds, but the cartilage of the bump lends for a better shape in many cases—and then an onlay tip graft to give additional projection, if needed.

What does he think about closed endonasal rhinoplasty versus open external rhinoplasty?

“Not every ethnic nose needs to be open. Some older surgeons don’t use open approach,” he says. “There has been a considerable trend in the last 15 years to use the open approach. I was trained with both, but I don’t use one exclusively over the other.

“For example, a Middle Eastern patient needing bump reduction and tip support can be served well with endonasal. If the patient is African American with no tip support and a flat dorsum, then open is more appropriate to address those goals.

“There is a role for both approaches,” he continues. “Physicians can’t favor one approach over the other and serve the patient. It is most important to choose whichever approach is needed to get the job done right. Each patient is unique, and there are no absolutes. Surgeons need open minds and a variety of tools to treat patients appropriately.”

ETHNIC PRESERVATION RHINOPLASTY

This is the most difficult aspect of ethnic rhinoplasty, according to Rizk. “All faces have a different shape, and the nose has to fit that face,” he says. “Plastic surgeons learn guidelines that give boundaries depending on facial proportions, but there is definitely a certain element of artistry that needs to take place.

“You really have to examine the impact on the rest of the patient’s face. If you make the bridge higher, it might make the eyes appear too close together, for example. There is a definite balance between patients wanting to preserve their ethnicity and wanting a good rhinoplasty. Today’s ethnic patients don’t want a Caucasian nose.

“There is a definite trend toward looking better and keeping their ethnic identity intact. Plastic surgeons with ethnic patients need to look at the whole face—chin, cheekbones, and width of face—and then make a custom nose that fits properly and creates facial harmony. This isn’t learned in medical school or even in residency—it’s all about intuition.

“Guidelines don’t always apply in ethnic patients, so it is important to understand the structures and use some artistry. It’s a lot like cooking. Give two chefs the same ingredients, and they will create two different dishes based upon their own artistic interpretation.”

Schae Kane is a contributing writer to PSP. She can be reached at [email protected].