|

Many of today’s surgical procedures are far less invasive and involved than their predecessors—so much so, in fact, that patients will try to seek out the easiest and quickest means for treatment. Such is the case with laceration repairs, even though seeking out the easiest and quickest treatments may mean the patient does not receive the detailed and precise expertise available from the best-qualified medical professionals.

“This is one of those areas where it’s really important for plastic surgeons to stay involved because we can really utilize our expertise to provide the best outcome for the patients, in terms of their healing,” says Kaveh Alizadeh, MD, FACS, a plastic surgeon with Long Island Plastic Surgical Group based in Garden City, NY.

“A lot of people think the quickest and easiest thing will be coupled with the best result, and that’s not necessarily true,” Alizadeh says. “The best result may involve a lot more complicated procedures. They may take longer to heal, but they will give you the best results—as opposed to the quickest, most painless thing. That may be better in the short term, but does not really give you the best results in the long term.”

What Lies Beneath

Most laceration repair cases come to plastic surgeons via the emergency room, although some are referrals from other physicians or even directly from the patients.

Obviously, the first step in preparing to repair a laceration is ensuring that the patient is stable. Associated with traumatic or accidental lacerations may be more severe injuries that can be life threatening.

|

|

|

|

| Kaveh Alizadeh, MD, FACS | Walter L. Erhardt, MD, FACS | Loren S. Schechter, MD, FACS | Todd Pollock, MD, FACS |

“That’s where the evaluation with the emergency room physician and maybe the general surgeon comes in, if it’s a multiple-trauma-type patient. You have to deal with all of those issues,” says Walter L. Erhardt, MD, FACS, a solo plastic surgeon in Albany, Ga.

“In the cascade of dealing with a multiple-trauma patient, dealing with lacerations is low on the priority scale,” says Erhardt, past president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, and currently chair of its public education committee.

Once a patient is deemed stable, the next step in the laceration repair is assessing the nature and extent of the injury and its impact on the tissues by taking a history and performing a general physical inspection of the wound, looking at the anatomic and aesthetic structures that are involved.

The approach used for the actual repair depends on such factors as the nature of the injury—including whether it is from a bite, fall, accident, or something else; whether it is a clean wound or contaminated with foreign bodies; and its location.

“What we do depends on the nature of the situation,” says Loren S. Schechter, MD, FACS, a plastic surgeon who practices in Morton Grove, Ill. “There’s not one stock answer for everything, which is common in plastic surgery.”

Straightforward wounds usually entail the use of local anesthesia, such as lidocaine. Often, especially for injuries to the face, lidocaine is used in conjunction with an epinephrine mixture to help minimize bleeding.

“There are certain fallacies about the use of epinephrine, especially on the face,” says Todd Pollock, MD, FACS, a plastic surgeon at North Dallas Plastic Surgery in Dallas and Allen, Tex. “People are taught in textbooks that you shouldn’t use epinephrine on end-organ blood supply, like the nose and the ears. The reality is that it is essential for good closure to use epinephrine in your local anesthetic to be able to get good visualization for your closure.”

Before & After |

|

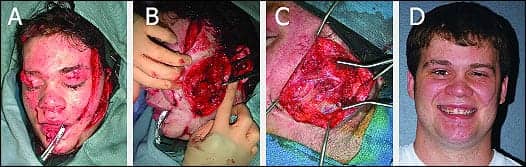

| A and B: This 17-year-old male was involved in a serious automobile accident. He sustained significant soft-tissue facial injury to his face with transection of his facial nerve. C: He underwent repair of the lacerations and sural nerve grafts to the facial nerve. D: He is shown 1 year following repair. Photos courtesy of Loren S. Schechter, MD, FACS. |

For more extensive injuries, sedation or a general anesthesia may be used. If the injury is in a difficult location or is very widespread, a visit to the operating room may be needed. After the local anesthetic is injected, a more thorough inspection of the wound can be made.

To clean the site, irrigation is performed, usually using saline or an antiseptic solution such as povidone–iodine. For a grossly contaminated wound, a pneumatic pulse lavage can be used to remove the foreign bodies.

The next step—and an important one, experts say—is to sharply debride the wound, removing any devitalized tissue to get the best clean closure, the best repair, and ultimately, the best scar possible.

Keep It Simple

The equipment used for straightforward laceration repairs most often includes a needle holder, forceps, suture material, and scissors. More complicated wounds may require additional equipment, such as cautery or retractors.

“You can do an awful lot of plastic surgery with just a needle holder and some thread,” Erhardt says. “I don’t drag out a lot of fancy equipment for repairing lacerations. It’s washing it, getting it clean, and putting some stitches in it. Obviously, if you have broken bones, you have to deal with those; plates and screws and pins are certainly appropriate there.”

Before & After |

|

| A: Six-year-old female patient following a dog bite. B: Intraoperative photo, demonstrating the extent of the injury. C: Patient 3 months postprocedure, after first stage of repair. Photos courtesy of Kaveh Alizadeh, MD, FACS. |

Whereas glues and staples can be and are used for certain laceration repairs—and are perhaps the preferred choice for patients—most plastic surgeons still rely on suturing the wounds for the most favorable outcomes.

“Even though there are things that may appeal to patients—such as a glue—in reality, they’re not giving you the best control over the scar, which may mean you may not have the best result possible,” Alizadeh warns.

“A glue can be applied by a pediatrician or emergency room physician who doesn’t really know the plastic surgical techniques. You may get a closed wound, but it may not look that different than if you had let the wound close by itself; whereas, when you have plastic surgical closure, you know you’re getting the best repair possible.

“I feel that I can have better control of the wound with more exact approximation of the wound edges with sutures versus glue, which is not exact, or staples, which are essentially a one-layer repair,” he continues. “I’m being called in because of my expertise to provide the best scar possible, and the best scar possible comes from the best, most exact approximation of the edges of the skin. I know I can provide that by putting in very, very meticulous sutures that are at the exact depth and distance that I’m looking for every time.”

Whereas the use of sutures is preferred in almost every situation, there are times when staples or glues are used, including when the laceration extends into the hair.

“Staples are pretty good to use in the hair because there is less trauma applied to the hair follicles, and so you have less injury to those hair follicles and less chance of scarring alopecia,” Pollock observes. “Skin glues have become popular; I think they are a shortcut that’s often overused,” he continues. “In most cases of full-thickness wounds, the best way to repair them using glue is to put deeper sutures in to take the tension off the wound, close up the dead space, and then use the glue on the surface. When I am using sutures on the skin, I try to minimize the number of sutures that actually go through the skin and try to use as much in the way of subcuticular sutures as possible to avoid any stitch marks.”

A Multilayered Approach

For routine, straightforward lacerations, repairs may simply entail the skin. For more involved wounds, in which multiple layers of tissue are injured, a layered closure may be needed. “I almost always will close in multiple layers to reapproximate the different layers of tissue and to close up any dead space to avoid any hematomas or fluid collections, which could lead to infection or wound dehiscence,” Pollock says.

Before & After |

|

| A: This 52-year-old male sustained traumatic subtotal amputation of the right ear from an automobile accident. B: Patient 6 months after surgical repair with the aid of leech therapy. Photos courtesy of Kaveh Alizadeh, MD, FACS. |

Absorbable, monofilament sutures are usually used for the deeper-layer repairs, whereas very fine, nonabsorbable, monofilament sutures are usually used on the epidermal layer of the closure.

“It’s a well-known, documented fact that the less tension there is across a wound bed, the better the healing and the better the scar,” Alizadeh says. “By successively putting multiple layers of fine sutures in a wound, we’re able to take the tension away from across the wound bed and distribute that across the scar, which will then provide better, more uniform healing and repair.”

The repair of a straightforward laceration in an adult can take as little as 30 minutes, whereas very complex lacerations can require a visit to the operating room and take a few hours to repair.

Risky Closure

There are, of course, risk factors and contraindications to consider when performing a laceration repair, including whether the wound is grossly contaminated and the duration between the injury and treatment.

Grossly contaminated wounds are often best left open. “Certainly, human bites we don’t traditionally close. The likelihood of a human bite getting infected is far greater than an animal bite,” Erhardt says.

In instances in which a wound is left open, serial washings—for 24 hours to 1 week after injury—may be used to clean the area before attempting closure. The longer the time between the injury and the repair, the higher the risk is of infection.

“The general rule of thumb is after 6 hours, not to close a wound,” Schechter says. “We have more luxury with that on the head, neck, and face. Most people will close wounds well after that time period, especially clean wounds. But in wounds that are contaminated and there was a delay in seeking care, we would typically defer closing them at that time, so they may heal by secondary intention—local care with topical antibiotics and a bandage. Then it heals from the bottom up.”

Before & After |

|

| A: This 32-year-old female sustained a post-traumatic laceration after being kicked in the left forehead by a horse. B: Patient 6 months after open reduction and internal fixation of frontal-bone fractures, debridement, and three-layer repair of the overlying soft tissue. Photos courtesy of Kaveh Alizadeh, MD, FACS. |

For situations in which a significant amount of time has passed between the injury and time of treatment, but the lacerations can still be repaired, a fresh wound may need to be created. Once a wound is re-created, all the tissue that was subjected to an infection or a foreign body can be removed, leaving a fresh wound that is as clean as possible. The plastic surgeon can then approximate that wound so it heals better than it would have had it been left alone.

“From my perspective, a surgical wound has a better chance of having an optimal scar than a wound that has been left to its own devices to heal,” Alizadeh notes.

A Scarring Experience

Aftercare instructions typically include avoiding direct sun exposure; keeping the area mostly dry; using ice packs to reduce swelling and discomfort, a topical antibiotic, and a bandage; and cleaning the wound with mild soap and water, saline, or even peroxide. For head and neck injuries, patients are also usually instructed to elevate the area.

Dressings are almost always used—with the exception of when a suture line is on the lips, where it’s difficult to provide a dressing. In those cases, a topical antibiotic ointment can be used on the lips. The terms of follow-up depend on the nature and magnitude of the injury, concerns about infection, and other factors.

Beyond concerns about the injury and repair, patients are also usually worried about scarring. Any time there is an injury to the skin—whether from a laceration or from surgery—it leaves a scar.

Erhardt says, “We can never totally control the situation or control the healing when we’re dealing with a trauma situation, because the incident is controlling how it’s going to heal—not what we do.”

“One of the misconceptions is that plastic surgeons keep scars from happening, and that’s not right,” he says. “We have techniques and skills that we use to try to minimize the scars, but any incision heals by forming a scar; that’s just the way it is.”

Schechter adds, “In elective settings, we try to disguise or conceal the location of the scars to make them inconspicuous. With a laceration, we don’t have that luxury. We have to deal with the situation that we’re given, so the scar may depend on the location, the degree of tissue injury, the amount of trauma, whether there is contamination in the wound.”

There are many things, however, that can be done during and after a laceration repair to help improve the wound. The removal of foreign bodies, the use of layered closure, and patient compliance with postoperative care instructions help to minimize scarring. There are also a variety of scar treatments on the market, including topical ointments, that may provide some benefit.

Alizadeh uses silicone sheeting to aid scarring, and, in very difficult cases in which there is hypertrophic scarring, he uses a steroid injection of triamcinolone acetonide.

In certain circumstances, particularly when the blood supply is tenuous, leeches can be used to suck out excess blood and help circulation. “Especially when you’re dealing with end-point organs—such as the ears, fingertips, tip of the nose, lips—for those areas, the leeches come in handy while the wound is undergoing the healing phase,” Alizadeh says.

Depending on how the wound heals, a patient may choose to have scar revision at a later time. It takes approximately 1 year for scars to fully mature.

Payment Due

One final consideration for the plastic surgeon who performs a laceration repair may be payment for the procedure. For emergency room cases, the decision to use a plastic surgeon is usually at the discretion of the emergency room physician, unless a patient specifically requests one. In situations in which a plastic surgeon is not a contractual provider for certain insurance plans, the patient may be responsible for a portion of the bill.

“Patients may not understand that they can receive additional professional fees from the plastic surgeon that may or may not be covered by the insurance company,” Schechter says.

“It’s important for patients to understand that there are cases that can be treated by emergency-room physicians who are trained to handle certain degrees of complexity. When patients choose to have a plastic surgeon, they may be responsible for additional fees from that plastic surgeon. They should ask questions, and be aware of it,” Schechter says.

|

| See also “Preemptive Strikes” by Danielle Cohen in the May 2007 issue of PSP. |

One thing is certain, according to these experts: Dealing with insurance companies may be their least favorite aspect of laceration repairs.

“Insurance companies will provide the lowest common denominator, and they will pay the lowest common denominator,” Erhardt says.

Adds Pollock: “Sometimes, the insurance for lacerations doesn’t pay for the amount of gas that it takes to get you there.”

Danielle Cohen is a contributing writer for Plastic Surgery Products. For additional information, please contact [email protected].

The Pediatric Patient

Performing laceration repairs on pediatric patients requires skill of hand—and a little bit of psychology. “I think it’s treating the parents as much as it is treating the patient,” says Loren S. Schechter, MD, FACS, a plastic surgeon in Morton Grove, Ill. “It’s traumatic for the parents, so reassurance and follow-up care are important.”

“The child always feeds off the anxiety of the parents. If the parents look anxious or worried, even though the laceration may be a very simple, easy repair, it will develop into something extremely difficult,” says Kaveh Alizadeh, MD, FACS, a plastic surgeon on Long Island, NY. “And as a surgeon, you sort of lose control of the environment because you really can’t create an environment that’s suitable to a good repair, as well as create an environment of increased trust with the parents.”

Preparing parents for what’s to come during the procedure by discussing the details with them beforehand can help calm their nerves, and in turn, help keep their children calm. The parents can even become part of the surgical team. Asking them to talk to or even sing to the child while you work may help steady the nerves of both.

“With kids, you try to make it as pleasant for them as possible,” says Walter L. Erhardt, MD, FACS, of Albany, Ga. “On the other hand, you have to be able to have control of the situation; you can’t have a kid running around the treatment room.”

Some plastic surgeons prefer that the parents leave the treatment room before the laceration repair begins, so that the child is not affected by their presence. “The kids will listen to you and follow your instructions—even when they’re very young—a lot better than when the parents are there,” says Todd Pollock, MD, FACS, of Dallas.

Pollock often treats toddlers who he says are perhaps more accident-prone because of their unsteadiness and sheer curiosity about the world that surrounds them. No matter how old the child is, he says, plastic surgeons should show their younger patients “a certain level of respect.”

“Those children understand and can cooperate a lot better than most people often give them credit for,” Pollock says, adding that it’s best to be honest with children about what’s going on during the laceration repair—but he also plays down the procedure a bit while working on them.

Absorbable sutures may be used to avoid a follow-up procedure involving the removal of stitches. “Sometimes it can be rather traumatic to remove the sutures,” Schechter says.

In severe laceration cases, or when the child is too distraught to be calmed, sedation may be used.

“I have a very low threshold for taking children to the operating room and putting them to sleep,” Erhardt says. “While even that is a traumatic experience, it’s far less traumatic than being held down in the emergency room.

“It comes down to the fact that I’ve got to be in control,” he says, “and I’ve got to have the ability to have the precision that is expected.”

—DC