Cohen works to get adult stem cell therapies recognized as essential to treating many diseases.

Steven R. Cohen, MD, FACS, decided to become a physician for a very personal reason: When he was 6 years old, his uncle was killed in a diving accident. With the innocence of a child, young Cohen soothed his grandmother’s grief by promising her that not only would he be sure to keep himself safe, he would become a physician to help others.

Although his parents were supportive, they didn’t pressure him to fulfill that promise. Ultimately, though, Cohen ended up in medical school at George Washington University, pursuing a career in surgery.

THE HEART OF THE MATTER

Cohen’s focus was always on surgery, and, at first, he thought a career in cardiac surgery would be his goal. “Surgery is an active, performing art,” he says. “When I started my surgical training, I was surrounded by a lot of smart, competitive people. We were all intrigued by the new developments in cardiology at that time, including artificial hearts and transplants.”

He landed a prestigious position at the cardio surgery branch of the National Institute of Health (NIH) and continued his training. Later, Stanford University contacted him for a position in its heart surgery program, but Cohen had already decided to choose a different road.

One day, as Cohen was watching a PBS program on craniofacial surgery for children born with facial deformities, the sight of experts in neurosurgery and craniofacial surgery working together to open the cranial cavity and reshape the entire facial mask intrigued him. He was astounded by the results—after these procedures, children who would have otherwise been ridiculed or even ostracized in their communities appeared completely normal and would lead regular lives.

Until this point, Cohen hadn’t really had much exposure to plastics. As a cardiac surgery and general surgery -trained physician, his time was spent primarily in surgery working to solve immediate health issues and find solutions to patients’ heart-related problems.

Undeterred, Cohen and his wife decided that plastic surgery was an amazing specialty; he began to contact colleagues to gain the recommendations needed to begin training as a craniofacial surgeon. His background in heart surgery and the pressure of that specialty prepared him well, and he ultimately landed at the University of Pennsylvania in their Plastic Surgery program and then completed a Craniofacial Surgery fellowship at UCLA.

FINDING A HOME

Cohen’s background at the NIH and his experience in medical research helped to open doors, and he joined the faculty at the University of Michigan and worked as an educator for around 4 years. From there, he moved to Atlanta to join a team of physicians at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. At the same time, he entered into private practice at Atlanta Plastic Surgery, providing medical expertise to adults as well as children.

Cohen says his practice, Faces+, which is based in the San Diego area, has done well financially during the cash-strapped recession.

“We were able to be very successful in Atlanta, and we built the practice to about 12 physicians,” he says. “In the mid ’90s, lots of midsize practices were receiving offers from medical management groups, and we ultimately decided to sell our practice and I went on to pursue other opportunities.”

With a multitude of available options and relationships with medical institutions around the United States, Cohen and his wife decided to keep it simple—find a place where they really wanted to live, and then create an opportunity that made sense. The San Diego area had good weather, lots of well-known medical schools and hospitals, and a need for craniofacial expertise. A move back to the West Coast met their personal goals, and Cohen’s professional focus was well received by other medical professionals in the area.

In 1999, he became the chief of craniofacial surgery and surgical director at the Craniofacial Center at Children’s Hospital of San Diego. Today, the hospital has one of the busiest programs in the U.S. He is involved in the plastic surgery training program at the University of California, San Diego, where he serves as a Clinical Professor and directs the Rady Children’s Hospital and USCD Craniofacial Fellowship.

In 2003, Cohen founded Faces+, a full-service plastic surgery practice in the San Diego area. While some practices have suffered due to weak economic conditions, Cohen says his practice has done well.

Currently, he estimates that about 30% of his time is spent focused on craniofacial procedures, with the remaining 70% on cosmetic plastic surgery.

STEM CELL INNOVATION

With his focus on craniofacial surgery, Cohen has maintained a strong interest in research and innovation. Through his love for research, he has become well known in the field for his exploration of fat derived stem cells and their application in health care. “Plastic surgery and craniofacial surgery are really creative specialties, and I enjoy the artistry and problem solving required in plastic surgery,” he explains.

His research into the use of stem cells has led him to join with a group of physicians and researchers to create the Cell Society, a nonprofit, international organization founded to expand the global use of regenerative cell therapies through science, policy, and education.

“The goal of the Cell Society really focuses on education for the general public as well as for the medical community,” Cohen says. “While there seems to be a lot of information available about stem cells and their medical application, there are also a lot of misperceptions. Our goal is to document appropriate techniques in using stem cells and provide empirical data on results, so that patients and their physicians can make informed decisions about appropriate care.”

The Cell Society believes that adult stem cell therapies, appropriately employed, can battle a wide range of diseases, including soft tissue defects, heart disease, Crohn’s disease, chronic wounds, urinary problems, and stroke.

“We created the Cell Society to make it easier for patients, physicians, and advocates to find one another, as well as to help them locate the policy-makers and world leaders who can help adult stem cell therapies become recognized as essential treatments for a wide variety of diseases,” he notes.

THE BIG PICTURE

Cohen spent time in Japan when stem cell-enhanced grafts were first being used commercially as fillers.

“In the big picture of health care, the use of stem cells is still new,” Cohen says. “New things are typically encountered by opposition, and smart people don’t always agree. We all need to be respectful of the varying opinions and work together to find the applications for stem cell therapy that work.”

Cohen looks forward to participating in the development of appropriate stem cell therapies in plastic surgery, and also recognizes the potential of stem cells in life-saving treatments. “It’s really exciting to watch our knowledge of stem cells evolve,” he says. “It’s akin to the discovery of digitalis in a plant, but now we are looking in our own bodies to find solutions. We have amazingly advanced mechanisms of repair and surveillance and if some of these processes can be harnessed, we may be able to use them to treat a variety of different diseases.”

Cohen and the Cell Society look at the human body and its existing repair mechanisms, then find ways to safely capture those mechanisms and redeploy them to focus on disease and other conditions that require more intense healing. “That’s the really exciting part,” he explains. “Finding existing solutions in the human body and using them in another location for another purpose. That possibility makes me very enthusiastic about finding possible cures.”

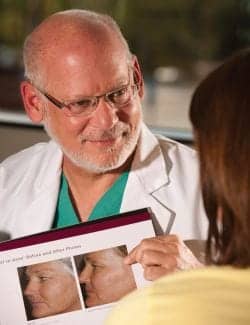

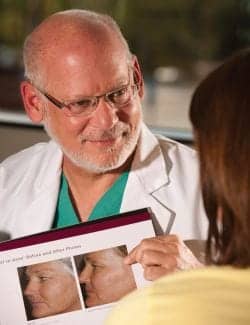

That is a long way from where Cohen started with stem cells. As early as 2003, when stem cells were first seen as a possible therapy for a variety of conditions, he was involved with an institutional review board study in which patients were injected with stem cell-enhanced fat grafts to remedy the effects of aging. The study looked at the longevity of the enhanced grafts and how they functioned as fillers. Cohen followed the results closely, and when stem cell-enhanced grafts began to be commercialized in Asia, he traveled there to learn more.

In 2007 and 2008, he spent time in Tokyo and started conversing with other health care leaders about starting the Cell Society—they recognized a need to educate the public and physicians about stem cells and address any existing concerns.

One of the early concerns associated with stem cells was related to breast cancer. Would stem cells used in cosmetic breast surgeries impact the likelihood of breast cancer? Would stem cells cause normal breast cells to turn into cancer cells? Today, thousands of women have had breast procedures, both reconstructive and cosmetic, using stem cell-enhanced fat grafts. However, in order to draw a statistically relevant conclusion, more data is still needed, he says. Early studies may indicate that women who have had cancer and complete the normal course of treatment, followed by a breast procedure using enhanced fat grafts, actually may have a reduced recurrence of cancer. “But to be certain, we will continue to collect as much data as possible,” he notes.

“The Cell Society is not taking the easy road. We are looking at known preclinical data and extending it to the clinical arena, to investigate the effectiveness and safety of these treatments and options in a controlled environment,” he says. The ultimate goal, he adds, is to create a “best practices” resource for practitioners when it comes to fat grafting and using stem cells.

DEFINING THE DREAM

Stem cells have so many possible applications, and Cohen has dreams about those possibilities.

“There is enormous potential to help stroke victims where brain tissue is at risk,” he says. “At the time of treatment, fat cells could be harvested, the stem and regenerative cells procured, and injected to the area to potentially reduce the infarct size and brain damage over time.”

Heart patients with congestive heart failure might be treated with stem cells to stimulate new blood vessels. Stem cells might be used to develop tissues in conjunction with tissue engineering—this tissue could be used to replace body parts. There have even been recent reports of using cardiac stem cells to create cardiac muscle.

Long term, researchers have identified the possibility of an adult adipocyte derived stem and regenerative cell “cocktail” that could enhance the body’s own healing power across a continuum of functions. It could be used to treat radiation injuries and other conditions where a more traditional treatment has yet to be identified.

Cohen acknowledges that on one hand the investigation and application of stem cells may seem like throwing everything and the kitchen sink at a problem, because some active ingredients are more appropriate and effective for particular conditions. “At the beginning, we won’t be able to dissect down,” he says, “but technology will evolve to make the treatments more precise. We will be able to develop appropriate cocktails for particular conditions.”

TODAY’S REALITY

Having natural tissue that can be used to enhance cosmetic procedures and that has other benefits that might assist with repair and rejuvenation. Stem cell-enhanced fat grafts may double the survival rate of normal fat grafts in breast augmentation surgeries, Cohen notes. Yet, he knows that these enhanced grafts won’t immediately replace implants—they will simply make an impact on how patients decide on their own best option in aesthetic procedures.

“Using stem cell-enhanced fat grafts in plastic surgery doesn’t seem to be that tough of a decision for my patients,” he says. “What can be safer then using the body’s own tissues?”

Schae Kane is a contributing writer for PSP. She can be reached at [email protected].