Summary: Non-white children experience significant disparities in access to and outcomes of cleft lip surgery, with delays, complications, and prolonged hospital stays being more common, largely due to health status, income, and location factors.

Key Takeaways

- Non-white children are significantly more likely to face delays, complications, and prolonged hospital stays after cleft lip surgery compared to white children.

- Disparities in cleft lip surgery outcomes are influenced by factors like underlying health conditions, income, and geographic location, rather than just race/ethnicity alone.

- The study emphasizes the need for surgeons to advocate for policies that promote equity in pediatric care, addressing both medical and socioeconomic disparities.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

Children of non-white racial/ethnic backgrounds experience significant disparities in access to and outcomes of surgery to repair cleft lip, reports a study in the November issue of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, the official medical journal of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS).

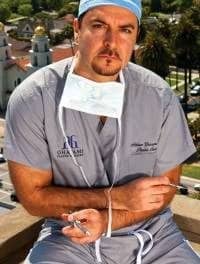

“Our data show that non-White children with cleft lip are substantially more likely to experience delays, complications and prolonged hospital stays than White children,” comments ASPS Member Surgeon Derek Steinbacher, DMD, MD, of West River Surgery Center in Guilford, Conn. “Importantly, our analyses also provide key insights as to why such disparities may exist in a historically safe and routine procedure.”

Discrepancies in Cleft Lip Surgery

Surgery to repair cleft lip and/or palate is performed to restore form and function in children with these common congenital malformations. In a previous study, Steinbacher’s group reported disparities in cleft palate care. The new study builds on those findings by assessing outcomes of cleft lip repair surgery in U.S. children of varied racial/ethnic backgrounds.

The analysis included 5,927 children who underwent reconstructive surgery for cleft lip (without cleft palate repair) between 2006 and 2012. Data were drawn from the nationwide Kids’ Inpatient Database. About 63% of patients were white, 22% Hispanic, 5% Black, 5% Asian/Pacific Islander and 6% “other” race/ethnicity. Timing and outcomes of cleft lip repair surgery were compared among groups.

Data analyses demonstrated that non-white children were more likely to have delays to cleft lip surgery (after age six months)—between 23% and 29%, compared to just 8% for white children. Non-white children were also nearly twice as likely to experience complications following surgery, and more frequently had prolonged hospitalizations, although the rates of both complications and prolonged hospital stays were low.

Surgery Delays Tied to Health and Income

The researchers used several stepwise regression statistical models to adjust for the possible conflicting influence of many other medical and sociodemographic factors. While some differences by race/ethnicity persisted even after adjusting for these factors—such as delays in surgery among Hispanic and Asian children—most seemed to be more closely linked to other factors.

For example, having more underlying medical comorbidities was associated with significant delays in care, increased postoperative complications, prolonged hospital stays and increased costs. Other contributing factors included patient income status and location in the United States.

Like the previous study of cleft palate, the results show that non-white children with cleft lip are more likely to have delays in care, complications, and prolonged hospitalization, compared to white children. However, “differences in baseline health status may account for much of this disparity in combination with factors such as income, insurance type and location,” the researchers write.

“Taken together, these data suggest a significant but complicated relationship between patient race/ethnicity and outcomes in cleft lip repair,” Steinbacher and his coauthors conclude. “The findings highlight the critical role of surgeons as advocates for policies and structures that increase equity in all facets of pediatric care.”