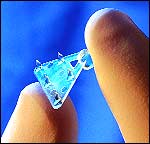

The Endotine Forehead device is designed for elevating the forehead tissue in browlift surgery, providing several points of contact with the elevated forehead tissue.

It helps to create a more even and gentle distribution of holding strength. Screws and sutures usually provide a single point of contact that may tear through the soft tissues, which would negatively affect browlift reliability.

A browlift (or forehead lift) repositions drooping eyebrows and softens creases of the forehead and between the eyebrows. In the traditional “open” browlift, an ear-to-ear scalp incision (bicoronal) elevates the forehead and eyebrow tissues, removes excess skin, and reposition the eyebrows. This incision leaves a noticeable scar, often with scalp numbness and a long recovery time.

For the “endoscopic” browlift, small 1-inch incisions are made behind the hairline, into which the physician inserts a small endoscope to detach the same tissues.

The forehead and eyebrows are then repositioned and held immobile by two small “endotine” devices. The endotine is a small triangular-shaped device that holds the tissues with small, sharp prongs. Once the tissues have healed, this device simply dissolves, leaving no scars.

|

| Figure 1. The Ultratine device holds tissues in position using small, sharp prongs. |

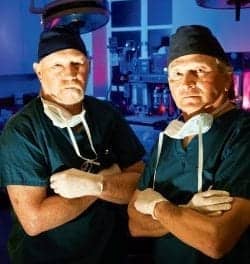

The Ultratine Forehead—a device used to secure soft tissue in brow and forehead lifts—is less visible and palpable than its predecessor, the Endotine, according to Cynthia Gregg, MD, FACS, a board-certified plastic surgeon with a private practice in Cary, NC.

Both devices are triangular, have five tines (3.0 mm or 3.5 mm long), a platform that is .5 mm thick, and a bone peg of 3.75 mm. The Ultratine, however, is different in one key respect: The constituents are a new blend of absorbable polymers that dissolve faster.

The Ultratine Forehead loses 90% of its strength in the first 60 days compared with 37% for the Endotine. Additionally, it loses 90% of its mass within 10 months compared with 12 months for the Endotine.

These features make the Ultratine ideal for thin-skinned or sensitive patients, Gregg says.

SURGICAL PEARLS

During the consultation phase, Gregg tells potential patients how the device holds soft tissue in place during the healing process, and that it may be visible for a period of time following surgery. In addition, she often demonstrates how the device works.

“Patient education is very important,” she emphasizes, “and saves a lot of questions afterward.”

Her endoscopic approach begins with four incisions: two just off the midline and two over the temples. (She places an Ultratine at each perimedian point to lift the central brow and forehead, and uses sutures to lift the lateral brows.)

“I use double skin hooks and lift the incision anteriorly, so when you drill the hole for the Ultratine, it’s in front of the incision location,” she explains. “Closing stitches are to the side of the device, causing less sensitivity and irritation for the patient.”

The Evolution of Bioabsorbable

Medical Devices

The use of absorbable tools in surgery is not a new concept. Records indicate that the Roman surgeon Galen used catgut to repair gladiator wounds during the second century.

Centuries later, in the 1960s, the market started moving to synthetic products, due to high infection rates associated with catgut.

The first absorbable devices in the cosmetic surgeon’s tool kit included sutures, screws, clips, and staples.

The Endotine Forehead, which first shipped in 2003, embodied a new concept: multipoint fixation.

By rethinking the problem, the Endotine Forehead’s creators had devised a way to spread the tension of elevated tissue over more territory.

The benefits included a reduction in the failure rate of forehead lifts and the elimination of complications associated with sutures—puckering and the cheese wire effect. In addition, physicians reported a decline in infection rates.

—RB

Finally, she advises surgeons to consider the location of the device in relation to the hairline. “I place it behind the hairline but in front of the closed incision. It’s less tender and less visible there.”

THE ULTRATINE STORY

Gregg was one of eight physicians who participated in a user-preference study after the FDA cleared the Ultratine in June 2006.

In total, 25 forehead lift patients with a median age of 55 were enrolled between July 2006 and January 2007.

The questionnaire asked participating surgeons about the device’s performance immediately after surgery, at 30 days, and at 90 days.

As of February 2007, results from the postop survey were tabulated. Questions centered on ease of use, engagement performance, and the critical issues of visibility and palpability.

In 18 of 25 procedures (72%), surgeons rated the device as not palpable or slightly palpable. In 25 of 25 procedures (100%), surgeons rated the device as not visible or slightly visible. This news was neither good nor bad, because traumatized tissue swells during surgery and can disguise a fixation device.

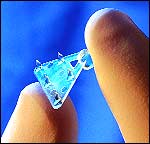

After the incisions were closed and the patient went home, the Endotine continued to grip soft tissue well beyond the 6 to 8 weeks required for biological healing before it slowly dissolved into the bloodstream.

Early users applauded the device, but complaints trickled in. Most revolved around patient dissatisfaction; people didn’t want to see or feel the device months after implantation.

|

| Figure 2. The Endotine grips soft tissue well beyond the 6 to 8 weeks required for biological healing before it slowly dissolves into the bloodstream. |

The manufacturer revised the Endotine, first slimming its profile and then offering a version with 3-mm tines for patients with thin skin.

Although the number of complaints declined, the manufacturer wanted to construct a new device that offered increased comfort for patients—without sacrificing ease of use during surgery or fixation performance.

This was, in essence, an engineering problem. The platform had to remain stiff enough to support small, sharp tines capable of puncturing and holding the periosteum, so it could not be reduced in thickness. In addition, the physical geometry of the device had proven itself in tens of thousands of successful surgeries.

The solution was in finding the perfect polymer—a material with a long history of use in the human body that had a master file with the FDA and a track record of safety and efficacy. In researching combinations of well-studied polymers, the manufacturer found a poly(l-lactic)/glycolide mix that looked promising. Subsequently, in vitro testing began.

When the product—now dubbed the “Ultratine”—earned the advisory medical team’s approval, more iterations were followed by FDA approval. Soon afterward, a limited number of the devices were sent to selected physicians.

USER-PREFERENCE SURVEY

The survey asked surgeons to rate the Ultratine’s performance on a number of issues.

At 30 days, with swelling eliminated, the device was only slightly palpable in 17 out of 22 cases, and palpable in five cases. Two months later, the numbers were significantly better. The device was no longer palpable in seven cases, slightly palpable in 14 cases, and palpable in only one.

Equally significant—at 30 days—surgeons reported that the device was not visible in 20 out of 22 cases.

In maintaining elevation of the forehead tissue, the results were identical at 30 days and 90 days. In 18 of 22 cases, surgeon responders said they were “very satisfied.” In three cases, surgeons said they were “satisfied.” There was a single “unsatisfied” response from a surgeon.

The results led to happy patients. At the end point, 20 out of 22 patients said they were satisfied with the results. One patient was not satisfied. The final patient was not reported.

IS THE CORONAL DOWN FOR THE COUNT?

An ongoing controversy in aesthetic surgery is how long the coronal forehead lift will survive, given the associated trauma; downtime; and the risk of nerve damage, numbness, and hairline recession. However, physicians face a difficult choice: Should they maximize lift with the coronal approach, or minimize complications via endoscopic surgery?

Gregg made the latter choice early in her career. “I initially used a 4-mm Mitek titanium screw that was left in place and relied on a suture to lift the forehead tissues. I then switched to the lactosorb absorbable screws.”

She now uses the Ultratine and Endotine devices, which “produce results that are closer to the coronal lift,” she notes.

“Every time I see a new technology, I have to think about ease of use, cost, the patient’s short- and long-term satisfaction, and long-term efficacy,” she adds.

Although the Ultratine devices add to the cost of a procedure, they provide noticeable results, can save time, and are less traumatic to tissue compared with other devices, Gregg notes.

|

| See also “Still the Gold Standard” by Angelo Cuzalina, MD, DDS in the September 2007 issue of PSP. |

Elaborating on the time-saving variable, she says. “I usually sit every patient up and take a look at least once during the procedure. Making an adjustment with the Ultratine is easy. It’s like Velcro. You lift the soft tissue and reposition it. That takes less time than pulling out a suture and reloading.”

ON THE HORIZON

Where are fixation devices heading? First, the obvious: All devices are becoming smaller and less invasive. In the future, they will be impregnated with coatings that stimulate tissue regrowth and healing. The new generation of devices will have to mass down much faster, and that will involve the creation and use of a new generation of absorbable materials.

“Wouldn’t it be terrific if the coating also reduced the effects of swelling and provided pain management?” is a common question.

Rebecca Bryant is a contributing writer for PSP. For additional information, please contact [email protected].