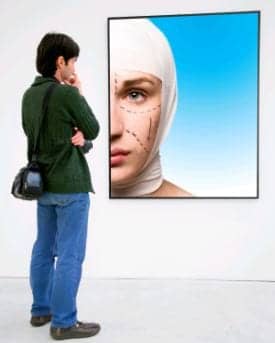

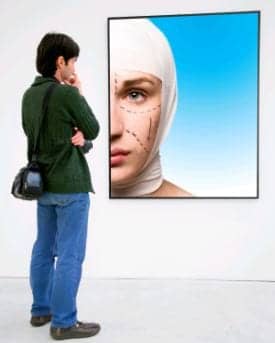

Doctor, I thought I wanted plastic surgery, but my best friend just had a facelift and she looks so strange. I can always tell when someone has had something done. It never looks right. I just want to look natural.”

This is a common quote heard multiple times in our offices every day, and it is not limited to surgery—you could substitute in Botox, filler, or laser treatment. Expressionless foreheads, overstuffed cheeks, and expanding lips hurt us all.

While we can try to deposit the blame on a few bad apples exercising poor judgment or out-of-field practitioners performing misguided treatments, maybe we should take a closer look at our current training modicums and state of affairs. Could there be an inherent bias within our core specialties deviating toward the unnatural? Has cosmetic medicine become distorted by a vocal minority?

Jacques Joseph, an orthopedic surgeon and one of the founding fathers of modern-day cosmetic medicine, was unceremoniously dismissed from his staff position at Berlin’s Charite hospital for performing “vanity surgery.” However, he knew that his art was rooted in psychology, not narcissism. By altering appearances, he could cause an improved self-esteem that allowed deformed or discriminated individuals the gift of passing back into society unnoticed and unbranded by physical inequalities.

A TOUCH OF CLASS

The ensuing 20th century heralded in better anesthesia, antibiotics, and advancing plastic surgery techniques paving the way to go beyond the unnoticeable. Recognizing the potential, the elite among our population took to cosmetic medicine, and it soon morphed into a tool for the upper crust to separate themselves from the underclasses.

Using beautifying treatments as a defining boundary of exclusivity is not a new practice. From Nefertiti’s kohl-highlighted eyes to Cleopatra’s wine resin baths, the ruling classes have always used expensive and exclusive cosmetic adornments to distance themselves. Celtic elites wore nail polish, and Marie Antoinette, along with her court of leisure, exhibited extensive hairstyles. And led by American movie stars such as Marilyn Monroe and her contemporaries, plastic surgery became the latest tool for defining class distinction.

Plastic surgery allowed overemphasis of sexually dimorphic feminine traits and further separated the starlets from the average citizens. Following in suit, the elite class, also wanting to appear better than normal, demanded cosmetic medical treatments. If the results were not entirely natural, that was acceptable because a new emerging class with expendable income was now showing off its privileged status. Today, these same behaviors are exhibited in the rising economies of the Middle East, Brazil, and Asia, where the recently indoctrinated walk the streets proudly with bandaged noses.

BEYOND NATURAL

Cosmetic medicine, complying with the desires of the distinct few, responded with more pulling, lifting, and liposuction in an attempt to recreate better somatic forms of youth. Concurrently, our blinding affair with better may have steered us on a path past natural to the supernatural.

While peering through the lens of effacement, we must admit something doesn’t look quite right when large, perky breasts of youth are placed on a small-framed middle-aged female or if a tight jawline is accompanied by thinning gray hair. Moreover, while a small petite nose doesn’t look right on an ethnic male face, nor does a large Romanesque nose look correct on a young Asian girl.

In isolation, these results often look great in photographs. In an attempt to display our aesthetic efforts, we may have flashed impressive photos at presentations or boasted our accomplishments in journals—resulting in backlogging of the “How I do it” sections.

In turn, young eager residents wanting to emulate their immortal mentors couldn’t wait to adopt bolder, newer techniques and mountain-moving procedures, but what was neglected to be mentioned or emphasized in our presentations or articles was outcomes. In other words, what were we actually achieving? Were we objectively achieving individuals who were more attractive? Were our interventions resulting in our patients projecting a more favorable first impression? Most important, were our patients happy?

This critical evaluation has been glossed over since Joseph’s time. Is there an inherent bias in our field to show bigger and better results in order to impress one another, but not focus on the task at hand? Shouldn’t our goal be to focus on what makes our patients happy? Should we temper our enthusiasm for newer and better techniques with our ability to improve feelings of patient self-worth?

Many times, impressive photos are from patients who are not happy with their outcomes. What is the point of showing a great result if the ultimate outcome of pleasing the patient has not been achieved? Sometimes, a different perspective is appreciated. Perhaps a closer evaluation at what makes someone appear and feel attractive is needed; and the social psychology and evolutionary biology literature is a great place to start.

BEAUTY AND MEANING

Does it surprise you to know that, “Subtle and hardly perceivable differences in faces are powerful enough to cause judgments of personality”? In a 2007 paper, Walker and Vetter showed that less than a millimeter change in the corner of the mouth, eyes, and nose can completely change the way someone is perceived.1 These small, isolated changes in facial features are consciously imperceptible to the unaware. However, once appreciated, it becomes glaringly overt to the trained eye.

In another relevant article outside of our literature, Joel Winston showed that when unknowing observers were asked to judge the age of attractive individuals, their reward centers in their medial orbital frontal cortex and medial prefrontal cortex were stimulated.2

Yet, more interestingly, when the observers were directly asked to evaluate the attractiveness of the faces, their reward centers were paradoxically understimulated. This “a-ha” moment suggests that if we have to consciously think about beauty, we are not rewarded by it. In other words, for a beautification effort to be successful, it has to purpose its effect in a subconscious manner.

Studies within our literature support the findings of social psychologists and evolutionary biologists that mild augmentations and alterations to the corner of the mouth, tail of the brow, or angle of the nose via surgery, neurotoxin, and/or fillers results in an individual projecting a more favorable first impression.3-5

However, the essential element is that the effect has to be natural appearing and subconsciously perceived. When facial makeup is placed in moderation, women are perceived more favorably. They are rated negatively when it is placed in excess.6 It is the small, seemingly unimportant effects that positively and significantly alter the appearance one projects and the judgment received.

We are just beginning to recognize that the mild alteration in appearance and resulting improved projected impression may be more heavily influenced by a deeper psychosomatic indirect effect than our intervention. The scientific evidence that expression and mood are codependent is clear.7 The inability to contract corrugators and frown along with turning up the corner of the mouth promoting a smile likely sets off a cascade of neurochemical events resulting in mood elevation.

Other factors—such as adequate sleep,8 proper diet,9 and moderate sun exposure10—not only result in an improved physical appearance but also fuel mood elevation. At times, the much better-appearing after photograph in our presentations might be more due to the homogenous tan skin in the well-rested, happy individual than our physical intervention. Likewise, a tired, pale, and stressed individual in our after photos may not look so impressive despite a successful facelifting procedure to reduce jowling and redundant neck skin.

It is the confluence of multiple factors that may be the difference that leads to an after photo looking better and ultimately to a happy patient.

The key to projecting a more favorable impression is that the alteration is not consciously recognized. Even the slightest evidence that something is cosmetically altered tips off the primitively encoded subconscious mind that something has been done, resulting in the opposite effect of that which was intended. It is why Michael Jordan looks better bald than with a receding hairline and why a well-done nose that does not fit the face makes a patient look worse.

REVERSING PSYCHOLOGY

Unfortunately, it seems that within our training, we may overlook the psychosomatic and image-enhancing benefits of slight, strategic, and covert cosmetic alterations. In order to evidence our results, whether in our journals or in our presentations, it becomes necessary to emphasize our morphological accomplishment. This focus may lead to a perpetual bias within our own field. We push to see and show obvious changes when maybe we should spend time highlighting the subtleties that our eyes and primitive brains find attractive. It isn’t a coincidence that our patients are asking the same of us—that is, less is more.

Many disparage the well-known clinics that advertise and perform branded facelifting surgery at an economical price. However, you would have to be rather naïve to dismiss the ingenious marketing efforts to capture exactly what the consumer wants.

While any product, regardless of quality, can achieve immediate success with extraordinary marketing, poor products eventually fail—although the last time I watched TV they still seemed be to very successful.

It would be short-sighted not to realize the winds of change are upon us, and our academies and societies have to appeal to the majority wanting minimally invasive changes. These are changes that result in subtle, yet effective and natural improvements.

As much as our hard-earned and well-deserved egos want to believe that our educational status, techniques, and hands are the most critical component to success, our victories both individually and collectively are deeply rooted in patient satisfaction.

As Chung has previously demonstrated, the most important predictor to patient satisfaction in outpatient plastic surgery is not the technical skill of the physician, but rather those factors that relate to efficient clinic operation and, most importantly, the quality of the patient-physician interaction.11 Likewise, it is not at all surprising that within 10 seconds, a surgeon’s tone of voice and communication style during routine office visits can be directly correlated with their malpractice claims history.12

Often, graduating fellows and emerging aesthetic physicians ask, “What is the secret to getting busy?” And rather than a unique technique or specific product/device, the answer is more of a philosophical one and seems deeply rooted in an ability to understand what makes a person feel attractive and why.

The better we train, the higher we all rise. So much time is spent teaching and learning technique, and so little time is spent on the intangible components of being successful both individually and as a group. To avoid irrelevancy moving forward, incorporating lessons on what is beautiful and why—while recognizing our own inherent biases—may be the key to not only assuring better patient outcomes, but also to securing the successes of our core societies.

Steven H. Dayan, MD, FACS, is a double board-certified facial plastic surgeon and otolaryngologist in private practice in Chicago and a clinical assistant professor at the University of Illinois College of Medicine in Chicago. He can be reached at .

REFERENCES

- Walker M, Vetter T. Portraits made to measure: manipulating social judgments about individuals with a statistical face model. J Vis. 2009;9(11):12 11-13.

- Winston JS, O’Doherty J, Kilner JM, Perrett DI, Dolan RJ. Brain systems for assessing facial attractiveness. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45(1):195-206.

- Dayan S, Clark K, Ho AA. Altering first impressions after facial plastic surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. Sep-Oct 2004;28(5):301-306.

- Dayan SH, Arkins JP, Gal TJ. Blinded evaluation of the effects of hyaluronic acid filler injections on first impressions. Dermatol Surg. Nov 2010;36 Suppl 3:1866-1873.

- Dayan SH, Lieberman ED, Thakkar NN, Larimer KA, Anstead A. Botulinum toxin a can positively impact first impression. Dermatol Surg. Jun 2008;34 Suppl 1:S40-47.

- Richetin J, Croizet J-C, Huguet P. Facial make-up elicits positive attitudes at the implicit level: Evidence from the implicit association test. Current Research in Social Psychology. 2004;9(11):No Pagination Specified.

- Ekman P. Does the face provide accurate information? In: Ekman P, ed. Emotion the Human Face. 2nd ed. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1982:56-97.

- Axelsson J, Sundelin T, Ingre M, Van Someren EJ, Olsson A, Lekander M. Beauty sleep: experimental study on the perceived health and attractiveness of sleep deprived people. BMJ. 2010;341:c6614.

- Hendrickx H, McEwen BS, Ouderaa Fvd. Metabolism, mood and cognition in aging: The importance of lifestyle and dietary intervention. Neurobiology of Aging. 2005;26(1, Supplement):1-5.

- Smith KL, Cornelissen PL, Tovée MJ. Color 3D bodies and judgements of human female attractiveness. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2007;28(1):48-54.

- Chung KC, Hamill JB, Kim HM, Walters MR, Wilkins EG. Predictors of patient satisfaction in an outpatient plastic surgery clinic. Ann Plast Surg. Jan 1999;42(1):56-60.

- Ambady N, LaPlante D, Nguyen T, Rosenthal R, Chaumeton N, Levinson W. Surgeons’ tone of voice: A clue to malpractice history. Surgery. 2002;132(1):5-9.