|

On your computer, pull up Google, and then type in the keywords “buttocks,” “implants,” and “Manhattan.” Of the 37,000 or so relevant Web sites Google retrieves, the first four listed will be those that belong to Douglas M. Senderoff, MD, FACS, solo practitioner and owner of Park Avenue Aesthetic Surgery, PC, in New York City.1

“If you own the Internet, you own the world,” says Senderoff, who contends that Web sites that land on page one of a search-results roster invariably enjoy the highest probability of being visited by cyberspace information-seekers. “Most people, when they search for something on the Internet, won’t bother clicking onto the sites that show up on the second page of found sites or on any of the pages after that. It’s human nature to assume that if a site is listed on the first page, it must be somehow better than any of those on the second page.”

And, by extension, it’s also natural for people to perceive those nearest the top of the first page to be inherently superior to those farther down.

|

| Senderoff reviews patient before-and-after photos with patient care coordinator Cheryl Verni. |

Optimized for Easy Finding

Senderoff—board-certified in plastic surgery, a diplomate of the American Board of Plastic Surgery, and a diplomate of the National Board of Medical Examiners—specializes in buttock implants, along with pectoral implants, breast augmentation (frequently performed endoscopically), liposuction, rhinoplasty, facelifts, abdominoplasty, eyelid surgery, breast reductions, breast lifts, cellulite reduction, and facial rejuvenation with calcium hydroxyapatite and botulinum toxin Type A. He also reports a brisk business in facial-filler procedures for HIV patients whose condition has led to severe lipoatrophy of the face.

The Internet first became a vehicle for Senderoff to promote his buttock-implant expertise—and his practice in general—at a time when the information superhighway was traversed mainly by computer geeks and had yet to emerge as a communications medium for the masses. Even so, he recognized its potential to reach people who desired to improve their appearance. “Right from the start, the whole purpose of my having a Web site was to generate qualified leads—and it still is,” he says.

The first Web site put up by Senderoff—he has added several since then—was handsome enough by the standards of that day and served as an impressive showcase of his capabilities. However, very few people who conducted a keyword search of the Internet ever found their way to it. “My site kept turning up way down on the list of finds,” he confesses.

Senderoff solved that problem by hiring a computer guru whose specialization was in the field of search-engine optimization—or SEO, as acronym-loving technophiles prefer to call it.

“The SEO specialist opened my eyes to how it would be possible to increase my visibility on the Internet,” Senderoff recalls. “Among the things she did was revamp my Web site’s coding to make sure the search engines would assign it a position as high up as possible on the list of retrievals. Also, she steered me away from overloading my site with graphics.

“A lot of plastic surgery Web sites make use of flashy animation, but animation improperly integrated can make it harder for a search engine’s crawlers to identify text content, which is what they use to come up with a ranking for the relevance of the site.”

When you get right down to it, though, a Web site—optimized or not for search-engine discovery—is only an initial point of contact for the consumer. From there, the challenge becomes one of converting those online visits into actual, physical, office visits and, eventually, the delivery of clinical services. That’s where a good staff comes in, Senderoff asserts.

“You have to be able to back up your Web site and other marketing tools with people who are cordial when they answer the phones and can talk in a highly informed manner about plastic surgery,” he insists. “Consumers want information immediately, and they want answers to questions immediately. If you can’t meet that need, they’ll lose no time in going to the next plastic surgeon on the list.”

Making His Practice Known

The Internet figures big in Senderoff’s marketing strategy—bigger, in fact, than it did in the early days of his practice. Back then, much of his marketing effort focused on display advertisements in newspapers and commercials on radio and cable television. His cash situation was such that he could not afford lavish television ads, so he strove to hold down costs by producing those spots on his own.

|

| Senderoff and physician assistant Inessa Shlifer discuss the plan for an upcoming surgery. |

“The first commercial I made was shot in the backyard of my parents’ house for about $500,” he says. “The message was very straightforward. It was along the lines of: ‘A new, more attractive you is easier than you think, and if you’re considering plastic surgery to improve your appearance, then come see Dr Douglas Senderoff.'”

Senderoff says he was careful to avoid making claims with these commercials. “The only thing I promised was to take the time to answer patient questions and be attentive to patient needs.”

The commercials ran night and day, and brought Senderoff a large number of cases very quickly. At the time he began to air them, the medical community had not yet widely embraced the use of broadcast advertising to promote individual physician practices.

“I definitely raised a few eyebrows,” Senderoff himself concedes. “But it was worth it when you consider how it jump-started my efforts to make a name for myself in a market as competitive and inhospitable to newcomers as Manhattan. Advertising is how any business attracts customers, and plastic surgery practices are businesses. If people don’t know you’re there, then you simply don’t exist as far as they’re concerned.”

|

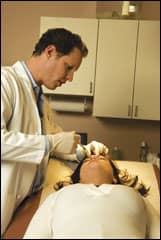

| Senderoff injects botulinum toxin Type A into a patient’s glabella area. |

In the Beginning

Credit for Senderoff’s existence as a physician belongs in no small part to his father, a successful New York cardiac surgeon. “It was my dad who inspired me to pursue a career in medicine,” he says. “I found his work fascinating.”

Enamored as he was of his father’s achievements, young Senderoff knew by the time he was a premed student at Atlanta’s Emory University (class of 1984) that a specialty other than cardiac surgery would be best for him. “I didn’t want to try to replicate my dad’s very successful career track, nor did I want to live in his shadow,” he remembers. “I wanted a field I could call my own, one that I would be passionate about.”

Plastic surgery soon caught his notice and seemed an ideal choice. “I liked plastic surgery because the results of surgery—the improvement in the patient’s quality of life—are typically seen immediately,” he says. “I also liked that in plastic surgery the patients tended to be very healthy and had a high degree of motivation to do the things necessary preoperatively and postoperatively to ensure a good result. Then, too, the procedures in plastic surgery usually involve delicate and intricate manipulations, which makes almost every operation an interesting challenge.”

Prior to going to medical school at the State University of New York Health Science Center in Brooklyn, Senderoff picked up a master’s degree in human nutrition from Columbia University. After obtaining his MD degree in 1989, Senderoff undertook general-surgery residency at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City, and he completed that program in 1994. The same year, Senderoff participated in a microsurgery research fellowship at nearby Mount Sinai Medical Center. Remaining there for plastic surgery residency, he was fully trained by 1997.

Senderoff then entered solo private practice. He chose to set up shop in Rye Brook, NY, in Westchester County, a short distance from his childhood home and about 45 minutes from Manhattan.

The first order of business was to obtain privileges at Westchester County hospitals, where he took as many emergency-department calls as he could handle. “Reconstructive work—that’s how I paid the bills during the time it took me to build up a volume of aesthetic cases,” he recalls.

To prime the pump for the aesthetic business he sought to develop, Senderoff soon thereafter opened a 1-day-per-week satellite in Manhattan, which consisted of space subleased from an established plastic surgeon. The addition of the Manhattan address imbued Senderoff’s practice with greater cachet—and he lost no time in announcing that fact to the world.

“I discovered that you have to promote yourself if you want things to happen,” he maintains. “You can’t sit back and wait for things to happen because, often, they never do—or, if they do happen, they come too late to do you the kind of good they might have at an earlier stage of the game.”

Senderoff explains that his goal during the early years of practice was not oriented around building income so much as it was geared to building a brand. “I was trying to get known as a provider who did good work and made patients happy,” he says. “I figured that if I could build the brand, the money part would flow automatically from there.”

Early Adopter

Senderoff’s practice grew at an impressive enough clip that he was eventually able to move the satellite to a 4,500-square-foot leased space on Manhattan’s Park Avenue South, which he then designated as his main office (an action that had the effect of recasting the Rye Brook office as the 1-day-per-week satellite).

The Manhattan office is as distinctive as it is classy. “I have the whole seventh floor, and the two side-by-side elevators open directly into my waiting room,” Senderoff says, adding that the décor includes elegant furnishings, fine wood floors, handsome wall treatments, and a crystal chandelier.

Behind the receptionist stand several shelves of high-end skin care products. Senderoff hints these could be harbingers of something bigger—such as a medical spa. “If you’re going to provide full-service aesthetic surgery, you can’t afford to ignore the nonsurgical components,” he volunteers. “Not so much for the sake of additional revenue, but to help retain patients.”

In-office procedures are part of Senderoff’s mix these days, thanks to his investment in an American Association for the Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgical Facilities–certified suite that consists of two operating rooms.

|

| Senderoff and operating-room manager Tanya Perez, RN, evaluate postoperative care instructions. |

“My facility allows me to very conveniently perform facelifts, breast reductions, abdominoplasties, and more,” he reports. “Rarely do I need to operate at the hospital anymore, even though I continue to be affiliated with nearby Beth Israel Medical Center. At Beth Israel, I mainly take emergency call and use the facilities there in the event I have an aesthetic surgery patient who is at risk of experiencing complications.”

Senderoff expresses a preference for being an early adopter of plastic surgery techniques and technologies. Of course, today’s cutting-edge procedures are tomorrow’s routine casework, so Senderoff vows to continue pushing the science-forward aspects of his practice and thereby always enjoy an edge in terms of clinical innovation.

“Providing quality care requires an embrace of the latest technologies, as long as there is good science behind them,” he firmly believes. “Consumers want what works.”

|

| See also “Gluteal Augmentation” by Douglas M. Senderoff, MD, FACS, in the May 2006 issue of PSP. |

As to making consumers aware of what works, a search-engine-optimized Internet will continue to rank highly among Senderoff’s front-line marketing tools. It is a safe bet that other plastic surgeons in his area will increasingly hop aboard the same SEO bandwagon, but that doesn’t seem to be a source of worry for Senderoff. The way he sees it, he has taken such a sizable lead with his own SEO strategies that the Web sites he operates are likely to always be at the head of the line.

Rich Smith is a contributing writer for Plastic Surgery Products. For additional information, please contact [email protected].

Reference

- www.google.com. Accessed February 6, 2007.