|

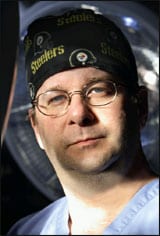

On a typical weekday morning, J. Peter Rubin, MD, FACS, wakes up at around 5:15 am, goes to his desk, and starts to answer e-mails and write his day’s to-do lists—there is always a lot to do.

Rubin has a long list of titles. The short list includes associate professor of surgery at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, founder and director of the Life After Weight Loss Body Contouring Program, co-director of the Aesthetic Plastic Surgery Center, co-director of the Adipose Stem Cell Center—all based in Pittsburgh—not to mention being chairman of the Plastic Surgery Research Council, based in Hanover, NH.

Essentially, Rubin is what you might call a “triple threat”—he is equally skilled as a teacher, researcher, and clinician.

Beyond those professional labels, one could also call Rubin a daddy to three young children and a husband to his wife.

He credits his supporters, students, and family for enabling him to handle it all. Ask him if it would not be easier to just have a private clinical practice in New York City or Beverly Hills, Calif, and he admits that it probably would.

However, Rubin truly loves all of his roles, and that is incentive enough for him to find ways to manage all of them and still get home in time for dinner.

INTEGRATING THE CLINICAL AND THE RESEARCH

|

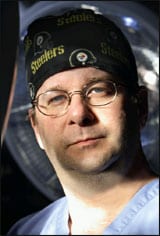

| A core team of specialists helps Rubin refine his surgical techniques inside and outside of the operating room. |

Rubin sees himself as being focused in one niche area of medicine: adipose tissue. It is that focus that allows him to thread his time and talents through so many events in the day.

“When you distill my clinical practice down, I’m working with adipose tissue on a daily basis,” he says. “I’m moving it, I’m shaping it, I’m molding it, I’m cutting it, I’m removing it, and so I have a very good working knowledge of how this soft tissue changes when being used in cosmetic and reconstructive surgery.

“I also see the clinical needs, which are that we need less invasive ways of making fat grow and making fat shrink, selectively. On the research side, I’m studying adipose biology, which helps to fulfill those needs. So, they’re very complementary.”

Rubin’s excitement for adipose tissue—and its potential to propel medicine forward and help his patients—has led to significant achievements in his clinical practice as well as his research.

Rubin’s relative youth—he’s only 42—may be another reason why he has the energy to be so involved as a teacher, researcher, and clinician.

With the increasing number of bariatric surgeries, Rubin’s body-contouring program, also highlighted in the book Body Contouring Surgery After Weight Loss, has been serving bariatric patients from all over the world.

As early as the 1990s, while he was in his training program in general surgery at Boston City Hospital, Rubin saw that body contouring was destined to be a growing field of medicine.

He subsequently spent time with one of the gurus of body contouring, the late Ted Lockwood, MD, at the University of Kansas Medical School in Kansas City.

“I spent just a little bit of time with him, but he was a person who really inspired me,” Rubin recalls. “He helped me to expand my thinking with how he analyzed these problems, how he thought about these cases. He would plan cases like slow-moving chess games, so that all of the components would come together. And it got me thinking about how to apply good principles in this area, so that you could develop new techniques.”

That training and thought process eventually led Rubin to create new procedures and new algorithms for body contouring, which he now teaches to his students and uses in his clinical practice. He also has written a textbook with Alan Matarasso, MD, titled Aesthetic Surgery After Massive Weight Loss.

Rubin is noted for several cutting-edge techniques for patients after massive weight loss.

In particular, he pioneered a new breast reshaping procedure and continues to lecture about his mastopexy technique.

“I’m getting rid of the epidermis on the breast and suspending the tissues in precise ways to the chest wall and reshaping the breast in this process of dermal suspension mastopexy,” he explains.

Breast reconstruction is only one aspect of Rubin’s body-contouring practice. Postbariatric patients have several challenges to overcome before he agrees to help them.

As part of his algorithms for evaluation and treatment, Rubin and his staff must consider the following:

- The patient’s nutritional status and how that impacts the surgery;

- The medical problems that accompany obesity and how to properly screen for those problems;

- How to help the patient decide what procedures they should have, while helping them to balance their expectations based on the results of these procedures; and

- How to help patients through the psychosocial issues of altered body image and their low self-esteem.

To meet these and other challenges, Rubin has put together a multidisciplinary team of nutritionists and psychologists, as well as developed access to weight-management specialists in the medical field.

This core team of specialists helps Rubin refine these techniques inside and outside of the operating room, as well as create a number of unique algorithms that ensure positive and consistent results.

“The core feature of my algorithms is that I keep patient safety absolutely number one,” Rubin says.

“One of my algorithms involves the fact that I won’t operate on these people until they’ve stabilized in their weight; I won’t operate during a period of active weight loss. Another principle is that the higher the patient’s body mass index, the less aggressive I will be with the operation.”

The lower the body mass index, the more Rubin can offer the patient in terms of quality of results as well as the range of procedures for which the patient would be well-suited and can also be done safely, he adds.

As an academic center, Rubin’s registry database is where he and his staff gather data about the patients and track their outcomes.

The data collected allows him to measure quality assurances, and also provides another way for Rubin to manage his various responsibilities.

“As you build the infrastructure, it’s self-maintaining,” Rubin explains. “For example, my core patient evaluation form/database form collects all of the information that I need for every patient. And because that’s standardized, I see all of the data that I need to see on every patient, and my staff works with that tool, also.”

Regardless of where Rubin is performing surgery, that standardization is extended to every hospital and for every procedure.

“That infrastructure is hugely important, because there’s no way I can do all of this by myself. I really rely on phenomenally good people who work with me, who can keep these systems running, and who will uphold the same standards that we all hold.”

|

|

| Rubin is noted for pioneering breast-reshaping procedures and continues to lecture about his mastopexy technique. |

THE ADIPOSE STEM CELL CENTER

Perhaps one of Rubin’s most famous accomplishments is the Adipose Stem Cell Center, which he co-founded with Kacey G. Marra, PhD.

Rubin and Marra’s adipose stem cell work has received national accolades and multimillion-dollar grants from the National Institutes of Health toward breast cancer reconstruction applications, as well as from the US Department of Defense, which commissioned Rubin and Marra to find ways to use adipose stem cells for craniofacial reconstruction in wounded soldiers.

“The big advantage to stem cells is that it’s your own tissue,” Rubin says, “The best reconstructive strategies or the best strategies to augment soft tissue involves using your own fat tissue rather than implants. Implants are great devices, but they have their own set of long-term problems that your own tissue doesn’t have.”

Rubin’s goal is to have a minimally invasive, injectable system based on fat stem cell technology that could be used for soft-tissue augmentation for a variety of purposes.

To accomplish this goal, Rubin’s laboratory is experimenting with adipose stem cells derived from a patient’s fat via liposuction.

The cells will then be stimulated in the laboratory to develop into specific types of fat and cartilage cells.

Once matured into the specific type of tissue desired, the newly grown tissue can be grafted—or cells can be injected—allowing the reconstruction of those areas using the patient’s tissue.

The laboratory’s early work was promising enough for Rubin to receive a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers.

This is the highest honor the US government gives outstanding scientists and engineers early in their research careers, and Rubin is the first plastic surgeon to receive such an honor.

|

See also “Adipose Stem Cells” by Richard Ellenbogen, MD, FACS, FICS, and Gary Motykie, MD in the December 2006 issue of PSP. |

Despite the accolades, Rubin is quick to credit Marra for both the laboratory’s accomplishments and for giving him the time and ability to pursue his other endeavors.

“While I have a background in tissue engineering and a clinical perspective, [Marra] brings a different perspective to the research,” Rubin says.

“She’s a polymer chemist, a tissue engineer by training. I bring a background in tissue engineering, as well as the clinical perspective,” he adds.

The next step for Rubin and Marra is the preclinical work—the in vitro and animal studies that are necessary to get FDA approval to start clinical trials.

They hope to start human trials within the next 2 to 3 years.

Tor Valenza is a staff writer for PSP. He can be reached at [email protected].