|

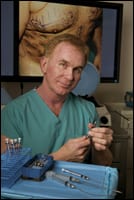

It’s a good thing that Sydney R. Coleman, MD, does not suffer from vertigo. Were he so afflicted, it would be difficult in the extreme for the New York aesthetic and reconstructive plastic surgeon to photographically document his cases the way that he believes yields the most useful results.

Coleman’s preferred style of shooting the body involves climbing a step stool and positioning himself above the patient so that he can see what the patient sees when looking down the length of the body. Not only does the view from this vantage point help Coleman better appreciate the patient’s self-perception of the problem or problems that brought him or her to his office in the first place, but also, it enables him to construct a 3D pictorial record of the patient’s physique.

“Your photographs of the patient must clearly demonstrate the defects,” he says. “That is not satisfactorily achieved by shooting from across the room. Shooting instead from above, you can pick up much more topographical information—the hills, valleys, irregularities, cellulite, everything.”

When taking pictures of the face, Coleman keeps his feet planted on the floor, squats, and aims his lens up. He then instructs the patient to tilt her head down—gravity does the rest, and that’s the view he wants. He also snaps a series of photos of the patient with the head turned first to one side and then another, his camera still positioned low.

Coleman says he also is at pains to take postoperative photos using the exact same lighting, lenses, and focal settings used for the batch he shot preoperatively. “You cannot produce before-and-after photographs that anyone will find believable if the two sets of pictures are taken in different rooms under different conditions with different equipment configured in different ways,” he cautions.

Superior Results

Coleman, who has practiced in Manhattan’s Tribeca district since 1985, is perhaps best known as the developer of a structural fat-grafting process called LipoStructure® (alternatively referred to in journal literature as Coleman fat grafting or the S.R. Coleman technique). He asserts that this process delivers results superior to those of injected collagen or silicone for restoring a supple, creaseless appearance to the face or body.

A typical LipoStructure procedure begins with the harvesting of fat from the thighs, waist, or other parts of the body where there are unwanted and unsightly accumulations of adipose tissue. These are collected by means of a blunt syringe with an attached cannula. Next, the harvested fat is placed in a centrifuge so that its oil, blood, and water content can be sedimented away.

“After refining,” Coleman says, “the fat is transferred to a smaller syringe and injected into the patient’s face or body in a very specific, layered fashion. The key is to deposit the fat in tiny parcels or aliquots—never in globs—so that each piece of fat has optimal access to blood and nutrients.”

Of equal importance is the planning process. “This is actually the stage where most of the mistakes are going to be made,” Coleman explains. “Not only do you have to decide where you will place the fat but also how much of it in each location. The changes that you’ll be making to the face or body are very subtle, measured in millimeters. So the detail of planning that’s involved is excruciatingly fine.”

Coleman’s interest in structural fat grafting traces back to his school days. “Fat grafting was one of a number of plastic surgery innovations being introduced back when I was in residency,” he says. “The problem was that no one had yet figured out how to make the grafted fat last any longer than injected collagen.”

Almost by accident, Coleman, then new to private practice, discovered how to conquer that shortcoming. Soon the procedure was much in demand among his growing patient base. Four years later, structural fat grafting accounted for half the cases he was seeing; and today, more than 95% of his practice involves the use of this technique.

|

| Coleman demonstrates his “over-the-top” patient photographing technique. |

Light on His Feet

Practicing under the banner of Tribeca Plastic Surgery, Coleman attracts patients on the strength of reputation but also with the help of solid credentials: He is board-certified in plastic and reconstructive surgery, and he is an assistant clinical professor at New York University School of Medicine. He holds memberships in the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, the Northeastern Society of Plastic Surgery, and the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. In addition, Coleman—a cofounder of the International Consortium of Plastic Surgeons and the Harry Buncke Microsurgical Society—maintains affiliations with New York Downtown Hospital, New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, and Manhattan Ear, Eye and Throat Hospital.

Patients also are attracted to Tribeca Plastic Surgery because Coleman has chosen as his practice partner Alesia Saboeiro, MD, one of the relatively few board-certified female plastic surgeons in New York City. Coleman says he appreciates the feminine perspective Saboeiro brings to aesthetic surgery in general and to his practice in particular.

“Dr Saboeiro has a comfortable, relaxed manner that puts patients at ease,” he relates. “Her empathetic nature allows her to focus on the individual concerns and needs of each patient. She brings to the table honesty in her opinions, drawn from her extensive training and experience with a wide variety of aesthetic facial, breast, and body-contouring procedures. She is the only surgeon whom I’ve personally trained in structural fat grafting.”

Fellowship-trained Saboeiro graduated from the University of Miami School of Medicine and completed general surgery and plastic surgery residency at Saint Louis University, where she subsequently taught and participated in academic practice before teaming up with Coleman in 2004.

|

| Coleman and practice partner Alesia Saboeiro, MD, evaluate a patient’s face for a potential facial fat-grafting procedure. |

Looking the Part

Outside of practice, Coleman enjoys an active lifestyle. “I’m big on fitness; I take a lot of fitness classes, and I lift weights,” he says. “I also engage in Pilates once per week—sort of a remnant of my days as a dancer.”

You read right. Coleman was indeed a dancer, and a good one at that during his days performing with the New Orleans Ballet. “This happened during my general surgery residency,” he shares. “I was in a production of The Nutcracker and several others. Then, when I completed general surgery training, I devoted a year to being a professional dancer, with some modeling on the side.”

Today, though, it’s only out on the slopes that Coleman gets to move his feet in serious ways. “I love skiing,” he enthuses. “Can’t get enough of it.”

It is evident why Coleman is so keen about exercise and sports: They give him a clearer mind along with the ability to avoid tiring during his long days at work. “I feel better when I’m physically fit, no doubt about it,” he says, adding that a toned body also plays directly into his ability to market the clinical services he offers.

“I’m selling health, whether it’s correcting a craniofacial deformity in a young person or simply helping an older adult become more attractive. That being the case, it only makes sense that I myself should be an exemplar of health.”

|

| Physician’s assistant Mary Lombardi and Coleman review a patient’s chart at the front desk of Tribeca Plastic Surgery. |

Charting a Path

Manhattan is a world or two removed from the Texas Panhandle ranch where Coleman was raised. Growing up there, he never really considered making medicine his choice of career until after his second semester at the University of Texas at Austin, when he took the Medical College Admissions Test as a low-priced trial run to gauge how he might fare on other exams for graduate school. “It only cost $25 to take the Medical College Admissions Test; all the others were more expensive,” Coleman recounts.

To his surprise, however, Coleman scored high on the medical school entrance exam—so high that his career counselor urged the 18-year-old to apply to the University of Texas medical school system and take the first steps toward becoming a physician. Coleman agreed to do so. He soon knew he had made the right choice.

In his first year of medical school, Coleman’s academic advisers arranged for him to participate in a project that involved interviewing younger teenagers who had sustained severe, disfiguring facial and hand burns. “My encounters with these children made me realize that their scarred faces interfered with their ability to communicate emotions and thoughts to the world around them,” he says, indicating that this is what put him on course to eventually opt for plastic surgery as his area of specialization.

“The experience also made me realize that trapped inside those disfigured bodies were some really important people. I became interested in trying to figure out how to get those people to look on the outside more like they did on the inside—in other words, so that their bodies and faces were a more accurate reflection of their souls than what the world was allowed to glimpse through the masks that had been forced on them.”

During his final year of medical school, Coleman took time out to travel abroad. He spent a good portion of his adventure in Spain, where he studied as an extern under the tutelage of several world-renowned physicians. Upon his return to the United States, Coleman was accepted at the Ochsner Foundation Hospital in New Orleans for internship and general surgery residency. He was there from 1978 to 1981.

“For a time, I became very interested in pediatric surgery,” he says. “It was very exciting work, and it seemed like it could be very gratifying. But what steered me back toward plastic surgery was I had a very difficult time witnessing the suffering of parents whose children could not be saved from death. I knew then that I needed to be in a field that would more consistently have positive outcomes.”

Criss-Crossing the Continent

In 1982, Coleman began a 3-year plastic surgery residency at Saint Francis Memorial Hospital in San Francisco. During this stage of his training, he studied aesthetic and craniofacial surgery with Fernando Ortiz-Monasterio, MD, in Mexico City, and completed a fellowship in microsurgery at the R.K. Davies Hospital in San Francisco. The Big Apple beckoned in 1985 when Coleman received an invitation to participate in a 6-month aesthetic surgery fellowship at New York University Medical Center’s Institute of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery.

Coleman quickly fell in love with the country’s largest city. “It was the center of the world,” he says. “I was awed by the wealth of art and diversity it offered, not to mention extraordinary social amenities in the form of nonstop access to incredibly interesting people. There is no place like New York on the face of the earth.”

Fine and good, but New York also happens to be one of the most competitive marketplaces for plastic surgeons—a place where it is crushingly difficult for young physicians to stay in business. Coleman, however, ensured the success of his budding practice by taking emergency-department call and performing plenty of reconstructive surgeries.

“It helped that I had microsurgical training and experience,” he says. “Back then, plastic surgeons new to town could not gain privileges at any of the big hospitals unless they had special skills. At the time, microsurgery was still relatively new, and few practitioners knew how to do it.”

Today, Coleman practices from a six-story converted industrial loft building he bought 4 years ago. His office occupies the first three floors and looks out across Duane Park, the city’s oldest public green. Contained within the ground floor of Coleman’s nearly 7,000 square feet of space is a two-room accredited ambulatory surgery suite that includes its own separate waiting area plus treatment and recovery rooms. Upstairs are his consultative offices, exam rooms, laser suite, and administrative areas. Fronting the street at the building’s main entrance is a Coleman-owned retail shop specializing in skin care products.

The Future Is Fat

Capturing Coleman’s imagination more and more these days is the medical potential for adult stem cells, an area of research in which he is actively engaged.

“A paper of mine was published last September on my findings that placement of fat under the skin does not just add volume, but actually over a span of 5 to 8 years improves the quality of skin pigmentation, texture, and suppleness, as well as in some cases reverses serious pathological conditions such as therapeutic radiation injury and steroid atrophy,” he says.

“In this paper, I reached the conclusion that these salutary effects may be produced by stem cells contained in the injected fat. This is not yet proven, but I am continuing my research in conjunction with New York University and other institutions where adult stem-cell research is being conducted.

“At this juncture, however, it appears safe to say that these stem cells in fat tissue are better thought of as repair cells and, as such, it may be that fat is as much a repair organ as it is an energy-storage, insulator, and cushioning organ,” Coleman continues. “And, evidently, it is when fat is harvested and then placed in another part of the body that these reparative effects become most pronounced.”

This and other discoveries about the properties of fat and their stem-cell components are helping convince Coleman that today’s medicine—plastic surgery included—may be dramatically different within a decade or two. “We’re talking about creating a branch of medicine centered around regeneration,” he says.

“Stem cell research to date, while interesting, has not been very fruitful with regard to changing medicine. But when we begin using stem cells derived from adipose tissue, we probably will be able to develop a system of regeneration of not just the skin but many other organs as well—heart and bone, to name just two.”

|

| PSP has covered fat-grafting procedures extensively in its Web news, most recently on April 24, 2007. For more information, search for “fat grafting” in our online archives. |

Coleman believes that his active role in adult stem-cell research could provide researchers with insights they might otherwise miss.

“The scientists engaged in all this research don’t have as strong an appreciation of the clinical world as perhaps they should,” he maintains. “That’s what I bring to the table—an outsider’s view. I’m in a position to be able to pose questions they might not themselves think to ask because of their lab-based focus. I can provide many answers for them because of my real-world clinical focus. To me, it’s very exciting to be able to engage with scientists and to do so through the lens of a clinician.”

Rich Smith is a contributing writer for Plastic Surgery Products. For additional information, please contact [email protected].