July 2010 Plastic Surgery Practice

By Amy Di Leo

A backpack and sleeping bag, river booties and a personal water purifier, a knife and a can of DEET—not the usual supplies a surgeon brings on an overseas pro bono medical mission, but this was no ordinary medical mission and no ordinary surgeon.

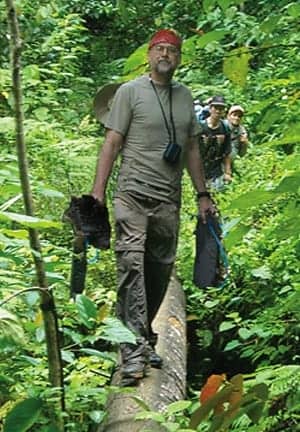

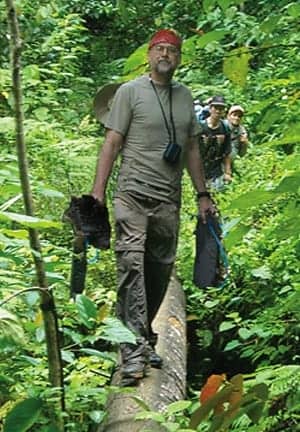

Just months before his 60th birthday in 2009, Indiana-based facial plastic surgeon Donn R. Chatham, MD, trekked deep into the most remote jungles of Borneo, Indonesia, on an 8-day journey with not much more than basic medical supplies and some survival equipment. He and three others are members of Chatham’s New Albany, Ind, parish, Graceland Baptist Church, and were the first Americans ever to visit this isolated region since the 1980s.

Anyone who knows Chatham—a well-known figure on view at aesthetic scientific meetings and conferences—has observed his tireless devotion to medicine and the aesthetic field in particular. His leadership and medical skills may be best summed up in the many scientific papers and panel discussions in which he has been involved, but his devotion to humanity and to developing the soul of the medical practitioner is something his peers observe in awe.

It is no surprise, then, that Chatham and his group jumped at the chance to visit Borneo at the invitation of an Indonesian man who was raised in one of the country’s remote jungle villages. This man, Chatham explains, had the unusual experience of having been pronounced dead by the village healer and then miraculously recovered. Eventually, the man left the village and became a pastor. Now affiliated with the international missions organization Mustard Seed International, the man wanted to go back in the hope of starting a small church in each village. “Indonesia is 95% Muslim,” Chatham says, “but the people of remote Borneo practice a form of ‘animism,’ perhaps more closely related to Hinduism.”

Ordinarily, physicians do not participate in these mission trips, but Chatham explains that the team requested a physician join them—it fit into the “Great Commission,” the Christian belief that Jesus Christ requested his disciples to spread his teachings to all the nations of the world. Chatham’s presence added another element to the trip for the villagers, who were able to consult with a physician about their ailments and any health concerns, though the team knew they wouldn’t be able to offer much in the way of medical treatments for the natives.

To prepare for the trip, Chatham did the immunizations, cardiac stress test, daily workouts, and hour-long hikes every day with a pack in the hilly woods. None of that prepared him for the oppressive climate, nutritional issues, and lack of sleep once he reached Borneo.

Chatham recalls that Indonesia intrigued and mystified him, in part because “it is the other side of the world, literally—a land that time forgot,” he says. “A simple but amazingly hospitable native people living in the most basic manner, with none of the niceties of life that I am accustomed to.”

The little advance knowledge Chatham had about potential dangers “was probably a good thing,” he says. At the end of the trip, their guide revealed that on an earlier trek to one of the same remote villages, a man who was half Chatham’s age collapsed and died at the summit.

What he did know prior to the trip was that his party would have to cross four rivers, endure hours of arduous climbing, and that their trip would land them in two very remote villages. Even then, the trek was really much more difficult than anticipated.

After landing in Borneo, the group’s leader, the career missionary, and eight Indonesian guides and interpreters set out for an 8-hour drive over a pothole-laden highway to the city of Batulicin. The next day was spent in the back of a pickup truck for another 6-hour drive until the road ended, at the small town of Cantung Kamen at the foot of the Meratus mountain range.

THE FOOT PATH FROM HELL

Chatham’s journey consisted of going up and down steep mountain trails; crossing dangerous ravines; traversing slippery log and bamboo bridges; trudging through mud, water, dense foliage, and past some of the world’s tallest tropical trees; and enduring often torrential rains, mosquitoes, and jumping leeches.

Chatham (with red bandana) with the inhabitants of an Indonesian village, deep in the Borneo wilderness.

Though surgeons are accustomed to dealing with leeches for medical purposes, the ones encountered by Chatham and his group were aggressively out for blood. It became a contest to see who could pull the most leeches off themselves. “Forty was an average,” he boasts, adding, “They are surprisingly very quick and hard to pull off. Their saliva has an anesthetic and blood anticoagulant, so you really don’t feel them much and the small wounds ooze for hours.”

By the ninth hour of the trek into the jungle, Chatham explains, he was getting discouraged and fatigued, wondering if there really was a village at the end of the trail. “I was aware that Borneo was home to Dayak tribesmen who once practiced headhunting, and your mind plays games when you are exhausted,” he says. “Our leader kept telling us the village was satu jam, which means 1 more hour to go. Yet, every hour he repeated this. We finally came to realize that this was just an expression that meant, ‘Keep on going; we are getting closer.’ Finally, at hour 10, we spotted huts by a river and our fear gave way to relief. We were greeted by very warm and gracious people.”

The villagers had seen photos of “white people” but had never seen one in the flesh. Though their hosts were extremely hospitable and gentle, they were also very curious and could not understand why the group had traveled all that way. A meal of rice, greens, and hot tea welcomed them. After dinner, they slept on the floor of a hut while curious villagers looked on.

“I was the only physician; and at each stop we conducted a clinic during the day and a worship service in the evening,” Chatham recalls. “Through an interpreter, the people shared their maladies and physical infirmities with me. For example: chronic pain from joint and osteoarthritis problems, often secondary to extreme physical demands of their lives, hypertension, headaches, dermatitis/rashes, gout, and visual complaints were common. There really was little we could physically do for most of them. However, we offered to pray—usually for strength and perseverance, individually with each patient; and all of them desired this,” he adds.

As part of his trip to the Indonesian jungle, Chatham hosted a medical clinic for villagers.

The village was made up of about 10 small huts and was located on a river, like all villages in the region. Chatham explains, “The river served as a) a water source; b) a bath and Laundromat; and c) a toilet. We quickly learned where spots A and B were.”

The villagers exist on very little, Chatham says. “Work is manual, such as farming or working the rivers for minerals. Huts are wood, and some have a solar panel on the roof, creating enough energy to power a small incandescent light bulb at night. Meals are prepared over an open, wood-burning hearth, and food consists of mainly rice and some greens. But one thing I noticed was that there was no complaining.”

The nearest store was in Cantung Kamen, via the trail that brought them into the jungle. While it took Chatham and his party a tedious 10 hours to make the trip, the average villager could make it in just 6 or 7 hours wearing flip-flops and carrying heavy provisions in a woven bamboo leaf basket on his back.

The trip itself became a bonding experience for Chatham and the other Americans. “We became a ‘band of brothers’ during the trek,” he recalls. “We relied on each other and gave each other encouragement, and will always have that bond that comes only from having experienced a life-altering journey together.”

STRENGTH, ENDURANCE, AND PRAYER

“One learns a lot about oneself when under extreme duress,” Chatham reflects. “Part of the trip created fears and apprehension for us, as we traveled deeper and deeper into the mountain jungles. One’s imagination can get wild. And it is a bit humbling to enter a new experience full of confidence, but then a few days later hit a wall and feel a bit broken.”

Chatham had hoped to travel to another village where he was told lepers lived—around a dozen people who had been ostracized by the larger village for fear of contamination. Unfortunately, heavy rains made those trails impassable, and the trip was cancelled. Chatham hopes that another party can make the trip someday to help those people.

The second village they visited was some 5 hours away and lay deeper in the valley at the conclusion of a very steep incline. Also located near a river, this village was a bit smaller. The food was the same—mostly rice, which was abundant, but here a rooster was killed for a special soup made in their honor. Chatham explains that the rooster’s feet apparently seemed prized. The missionaries were fed fresh coconut and some pineapple, as well.

The trek out of the jungle was one Chatham says challenged them to their physical and psychological limits. The night before they left, their Indonesian porters reluctantly revealed that it would be longer and more difficult than the trek in. The equatorial climate—combined with hydration and sleep-deprivation issues—exacerbated their exhaustion to create what Chatham calls a state “beyond exhaustion.”

Back in the United States, Chatham prepares for a day’s work at his Indiana clinic.

“Our trail consisted not only of vertical pathways, but we had to rappel down vines tethered to trees, cross logs angled into waterfall ravines, and maneuver slippery rocks, rivers, and streams,” he explains. “Crossing the rivers was actually the easy part. There were frequent slips and falls, but no fractures or serious injuries. There was no Plan B, no alternate way home, and no Medevac.”

People in the group “fervently prayed for strength and increased perseverance on the last day,” Chatham says, “and believe there was supernatural help that was present.” Ten hours after they started, they arrived in Cantung Kamen. After another 5-hour truck ride to Banjarbaru, they rested.

Several members of the group became very ill from dengue fever, malaria, typhoid fever, cracked ribs, twisted ankles, separated toenails, and body rashes. Thankfully, Chatham adds, everyone recovered.

IN REFLECTION

Reflecting on the trip, Chatham recalls a time when he slipped on ice in the cafeteria of his local hospital in 1995 and fractured his ankle so badly that it required plates and screws to repair it. “Sometimes, an experience will help to make sense of an earlier experience in one’s life,” he recalls. “I was always a bit bothered that this occurred in one of the ‘safer’ places while doing a routine activity: walking. The trails in Borneo were unforgiving, and while everyone fell at times—including me—I did not break anything.

Chatham’s talent as an aesthetic practitioner is well-known to peers and patients alike.

“So, while navigating the most treacherous place one could walk, I was spared any injury. Thus, there is a bit of yin-yang balance at work here. I now appreciate the blessing of breaking my leg at the best place possible and not breaking my leg at the worst place possible, where this likely could have become fatal. There is a peace about this now that probably could only have come about in this way.”

The trip to Borneo ended at a hotel in Java, “with a clean bed, fresh water, a bathroom with plumbing, and real food,” he reminisces about the “almost surreal, extreme natures of the journey.”

Chatham is convinced the mission was to enter this land where few outsiders had ever gone, but the mission included a return to safety. “Hopefully, what we brought to those two villages will, in some way, germinate into something deeper, but I do not expect to know when or how,” he says. “The other lesson learned was that no matter the depths of exhaustion or discouragement, there are powers, both physical and supernatural, that can combine to take an extreme situation and make it into a positive triumph.”

Back home, nearly 10,000 miles from the jungles of Borneo, Chatham has a quarter-century-long thriving facial plastic surgery practice with offices in Louisville, Ky, and New Albany, Ind, which is where he calls home. He spends his days outside of work enjoying simple pleasures, which includes raising two teenaged children with his wife, enjoying an active church life, pursuing his artistic talents, and occasionally fishing or hiking the trails of nearby knobs where he lives.

Both personally and professionally, Chatham is about as humble as they come, an attribute not often found in the plastic surgery realm. He says he hasn’t really shared the story of his Borneo trip with many of his patients. Like the people in Borneo who questioned what he was doing there, his own patients with whom he shares the story often look at him quizzically and ask why he would do that.

Why, indeed?

Certainly no stranger to helping others, Chatham grew up with a father who was a small-town family practice physician. It is clear how proud he is of his dad, who was also a missionary doctor and who passed away last year. Chatham accompanied his father on trips to Guatemala in the 1960s and later to other Central American countries to help the villagers, both medically and spiritually. “My dad was a strong influence on my values and behavior,” Chatham recalls. “I learned about charitable giving from him.”

He is instilling similar values in his son and daughter, as well. Chatham hopes to be able to take his kids on missionary trips when they are older and mature enough.

Although he does not know the full extent of how much he may have helped the people with whom he connected in Borneo, Chatham says, “The Indonesians were very appreciative that Americans would travel so far to try to help them, to minister to some of their needs, and to pray for them. Hopefully, we planted some seeds that will germinate and bloom in ways I will not likely understand fully.”

However, during the time Chatham and his group visited those remote villages, the villagers’ spoken thanks—or terima kasih—were as abundant as the rice.

Amy Di Leo is a contributing writer for PSP. She can be reached at [email protected].