Rhinoplasty may be the most difficult operation in plastic surgery—the anatomy is complicated, the building materials (bone and cartilage) are limited in their malleability, and postoperative forces of scar contracture may undermine surgical results, sometimes years following surgery. It is no surprise that rhinoplasty has one of the highest revision and complication rates of any operation.

Due to the vast breadth of approaches, techniques, and philosophies used in primary rhinoplasty surgery, a diverse array of complications have been described. Small asymmetries, malposition, and irregularities may occur as the result of minor errors of technique. These problems are generally straightforward and easily corrected.

Large asymmetries, functional obstruction, and gross deformities are likely the result of surgeon error. There are several categories of complications, each of which result from different types of surgical mistakes.

Patients who seek revision rhinoplasty may present with any number of these functional and cosmetic complaints. Identification, diagnosis, and correction of these problems depend on a thorough understanding of the surgical pitfalls and postoperative processes.

This article reviews the general categories of complications, highlighting the most common problems encountered during revision surgery. Common problems requiring revision surgery are outlined according to determinants of preoperative analysis. For any given deformity, the thickness of the soft-tissue envelope will determine how likely it may be detected and diagnosed prior to surgery.

|

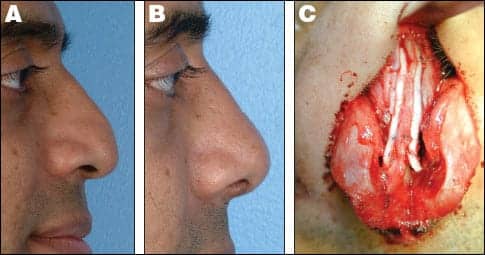

| Figure 1. Severe saddle deformity and collapsed nasal tip treated with undersized dorsal rib graft. Preoperative (A, C) and postoperative (B, D). Undersized dorsal graft removed (E); replaced with a large, strong dorsal rib graft and extended columellar strut (F). PHOTO COURTESY OF DAVID W. KIM, MD, FACS |

DORSAL PROFILE

Dorsal irregularity. Most commonly, this problem arises after contour irregularities are created along the bony and/or cartilaginous dorsum. Such irregularities may be addressed via rasping of the bone or shaving of the dorsal cartilage. For areas of mild to moderate deficiency, onlay grafting with crushed cartilage is indicated.

Low dorsum/saddle deformity. Increasingly dramatic dorsal abnormalities may result from overaggressive dorsal reduction and destabilization of the dorsal septum. This results in a dramatically “scooped” appearance on the lateral view, otherwise known as a saddle nose deformity.

In severe saddle deformities, rib cartilage may be necessary. The onlay graft is fashioned into a canoe shape, with the cephalic edge placed into a precise pocket over the bony dorsum.

The cephalic edge should terminate roughly at the level of the desired nasal starting point. The caudal edge should terminate in the supratip area. Ideally, the domes will project above the graft at its caudal aspect, providing a smooth transition from the dorsum to the tip.

When there is concomitant loss of nasal tip support due to caudal septal deficiency, the onlay rib graft must be supported at its caudal end with a strong, extended columellar strut.

A common error of omission during primary rhinoplasty for the correction of a collapsed saddle nose is the use of an insufficiently large or strong graft for correction.

Pollybeak. A pollybeak refers to an abnormality in which the supratip projects dorsally beyond the tip. This causes a rounded appearance to the tip, with a lack of definition and an absence of a supratip break or a columellar-lobular break.

Although the deformity creates an appearance of supratip fullness, the problem may be caused by one of several processes.

One possibility is the surgeon’s failure to reduce an overly elevated middle vault and supratip dorsum.

|

|

| Figure 2. Severe nasal tip bossae and lateral collapse from previous reduction rhinoplasty and dome division. Preoperative (A, C) and postoperative (B, D). Correction required tip reconstruction with shield graft and lateral crural grafts, along with crushed cartilage camouflage grafts (E). |  |

In a primary tension nose deformity, the anterior septal angle represents the most projecting point of the nose, with the tip structures “hanging” from this point.

Therefore, the dorsum at the level of the anterior septal angle must be reduced—or the tip brought out beyond this point—in order to establish a proper tip-supratip relationship. Failure to establish this relationship is an error of omission leading to postoperative pollybeak.

Paradoxically, excessive excision of dorsal septal cartilage may result in the same deformity. Particularly in patients with thick, inelastic skin, the skin-soft tissue envelope (SSTE) cannot redrape into the area of skeletal reduction. The tissue void fills with scar and fibrosis, resulting in a soft-tissue pollybeak.

Finally, if tip support is compromised and not reconstituted, the resultant tip ptosis may lead to deprojection at the tip and an appearance of supratip fullness.

These three types of pollybeak deformities require individualized methods of treatment.

Correction of untreated tension nose deformity requires completing the dorsal cartilage reduction and ensuring the presence of a stable nasal base, in order to maintain tip position relative to the dorsum.

Correction of soft-tissue pollybeak requires projecting the tip into the thick SSTE beyond the level of the supratip and dorsum. The pollybeak caused by tip ptosis mandates reestablishing tip support and returning the tip to its appropriate projection.

A variety of methods exist to stabilize the nasal base and restore tip position. As these strategies are quite different from one another, it is crucial to understand the etiology of the problem prior to surgery.

Palpation is critical in order to differentiate between soft-tissue fullness and cartilaginous excess. An acute nasolabial angle and a weak tip with little recoil will indicate the presence of tip ptosis that is secondary to loss of tip support.

MIDDLE VAULT

The middle vault poses one of the most difficult challenges in rhinoplasty. The separation of the upper lateral cartilages from the septum is a result of cartilaginous dorsal reduction—a common maneuver in primary rhinoplasty.

Failure to restabilize the attachments of the upper lateral cartilages and septum with spreader grafts will result in inferomedial collapse of the upper lateral cartilages, pinching of the middle vault, an inverted V deformity, and internal valve airflow obstruction.

Sometimes, unilateral collapse will occur, resulting in an asymmetrically pinched middle vault. Correction of these problems requires placing spreader grafts that are stabilized between the dorsal septum and upper lateral cartilages.

Asymmetries in this region may be addressed by utilizing spreader grafts, which are appropriately disparate in width.

LATERAL NASAL WALL

Some of the secondary rhinoplasty patient’s most common complaints relate to weak, unsupported lateral nasal walls. This complication gives the alar lobule a pinched appearance and can lead to a potential nasal valvular collapse.

|

| Figure 3. Tip ptosis and pollybeak deformity due to caudal septal truncation and loss of tip support. Preoperative (A) and postoperative (B). Treated with extended columellar struts, caudal extension graft, and repositioning of tip cartilages (C). |

Aggressive reductive techniques of the lateral crura, such as dome division and large-volume reduction, likely will create these problems. Thin-skinned patients with narrow, projecting noses are particularly predisposed to such complications.

Lateral wall weakness leading to valve collapse. The degree of valve collapse may vary in severity and typically requires structural grafting.

For isolated supra-alar pinching and collapse, the alar batten graft is the workhorse tool for correction. These grafts are curved cartilaginous supports placed into the area of maximal lateral wall weakness. Via the external approach, the grafts are placed into tight pockets, which overlap and extend laterally to the lateral crura.

The curvature of the graft should be oriented to lateralize the supra-alar area with the concave surface medial. The lateral aspect of the graft is usually caudal to the lateral crura, depending on the area of maximal pinching. In most cases, the grafts should extend to overlap the pyriform aperture in order to add support.

Alar pinching and retraction. Excisional techniques on the lateral crura may also cause weakness and contracture at the alar margin. These deformities may create visible deformity in addition to airway problems.

Cephalic retraction may cause alar elevation, which on the lateral view reveals excessive columellar show. Contracture from previous reduction of the lower lateral cartilage may also be evident on the base view as alar pinching.

Placement of alar rim grafts may restore support and create a more triangular nasal base. These long, narrow cartilaginous grafts are placed into precise pockets along the alar rim just caudal to the marginal incision.

These grafts will improve upon the concave or “knock-kneed” appearance of the rim on base view, as well as create a more triangular appearance to the basal view.

Severe cases of alar retraction may require the use of composite grafts of ear cartilage and skin placed into the marginal incisions, which is done in order to reposition the alar margins in a more caudal position.

NASAL TIP

At times, the most noticeable deformities in secondary rhinoplasty occur in the nasal tip. The challenge lies in modulating tip position and shape and then maintaining the modifications against the forces of scar contracture.

Tip deformities in secondary rhinoplasty patients come in all forms and may result from any of the classes of surgical errors described above. The external rhinoplasty approach in revision of the nasal tip allows for the unparalleled ability to correct asymmetries.

Irregularities, bossae, and pinched tip. Asymmetry of the tip may result from problems of unequal excision, suture modification, or grafting.

Subtle discrepancies may not become evident for several months until the edema resolves. Bossae may form as the result of knuckling or angulation of the lower lateral cartilage and tip grafts as the SSTE contracts. Patients with thin skin and strong cartilage are particularly susceptible to this problem.

Conservative cartilage trimming, revising suture modification of the domal cartilage, and/or onlay camouflaging may correct such problems.

The pinched nasal tip results from the excessive narrowing of the domes from excisional techniques, dome division, and/or excessive transdomal sutures. Lateral wall collapse and alar pinching may further complicate the narrowness of the tip. This unnatural, “operated” appearance is a sure sign of prior surgery.

Restoring a natural tip appearance may require reconstruction of the entire tip cartilage system with a shield graft and lateral crural grafts.

|

|

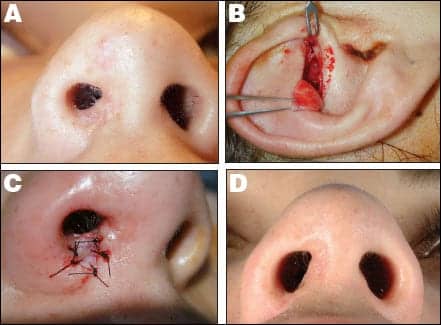

| Figure 4. Nostril stenosis due to cautery injury. Preoperative (A) and postoperative (B). Composite graft from cymba concha (C); graft interposed into area of nasal sill web (C, D). | |

Over-rotated (short nose). A short-nose deformity is frequently due to loss of the stability between the caudal septum and lower lateral cartilages. Aggressive excision of the caudal margin of the nasal septum and aggressive cephalic trim of the lateral crura can cause upward scar contracture and tip rotation.

Correction of this deformity may require repositioning the tip tripod structure in a more caudal position. This may be accomplished by pulling the tip cartilages caudally into the soft-tissue envelope, effectively lengthening the nose.

Typically, the medial and intermediate crura are freed from each other and repositioned caudally onto the caudal septum. Extended spreader grafts or a caudal extension graft may be necessary in such scenarios, in order to provide enough length to the septum.

During such procedures, a shield graft may also be placed to compensate for any loss of projection that occurs with the tip counter-rotation.

Ptotic tip. Maintaining tip position after rhinoplasty depends on restoring any tip-support mechanisms that are weak or have been surgically violated.

Separation of the lower lateral cartilages from the upper lateral cartilages, freeing the medial crura from the caudal septum, and excising or weakening the lower lateral cartilages, are common maneuvers in primary rhinoplasty that compromise tip-support mechanisms.

Stabilizing the tip tripod framework at the nasal base can help prevent the eventual ptosis of the unsupported tip and subsequent elongation of the nose.

Methods of base stabilization include suture stabilization of the medial crura onto a long caudal septum, a caudal extension graft, a columellar strut, or an extended columellar strut.

Failure to take such measures may lead to gradual loss of tip support, a hanging tip and infratip lobule, an overly acute nasolabial angle, and an under-projected, long nose.

In addition to the obvious appearance on lateral view, poor tip strength and recoil on palpation confirms the diagnosis. By using one of the base stabilizing techniques, the tip position and support may be restored.

ALAR BASE

One of the most difficult rhinoplasty complications to correct is an overly narrowed alar base.

Alar base reduction should be performed conservatively, with the aim of achieving 60% to 70% of an idealized reduction at the time of primary surgery.

|

| See also “Rhinoplasty Minus the Knife” by Steven H. Dayan, MD, FACS, in the February 2007 issue of PSP. |

Composite grafts harvested from the cymba concha work well to correct such deformities. These grafts are interposed into incisions placed at the areas of maximal narrowing. Such grafts are useful also to correct cicatricial nostril narrowing from previous surgery.

When the skin has been significantly damaged, the revision rhinoplasty surgeon must be exceedingly cautious in manipulating or undermining the SSTE.

Typically, this problem is caused by an infected or extruding alloplastic implant. In this situation, the implant should be removed, the infection controlled with antibiotics, the damaged skin envelope allowed to recover, and the contour restored with autogenous cartilage grafting.

If there is any doubt regarding the integrity of the SSTE, surgery should be delayed to allow full recovery. Blue discoloration or cutaneous telangiectasias signify damage and added risk for skin complications. In catastrophic cases, such as when the soft-tissue envelope has already been severely compromised, one should consider staged preliminary repair of the SSTE with skin grafts or local or regional flaps prior to any structural nasal surgery.

David W. Kim, MD, FACS, is director of the Division of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in the Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery at the University of California, San Francisco. He is double-board certified by the American Board of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and by the American Board of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Kim is also a fellow of the American College of Surgeons. He can be reached at (415) 885-7700.

REFERENCES

- Becker DG, Weinberger MS, Greene BA, Tardy ME. Clinical study of alar anatomy and surgery of the alar base. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:789-95.

- Byrd HS, Hobar PC. Rhinoplasty: a practical guide for surgical planning. Plastic Reconst Surg. 1993;91:642-656.

- Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ, Friedman RM. Classification and correction of alar-columellar discrepancies in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:643-648.

- Kim DW, Gurney TA. Management of naso-septal L-strut deformities. Facial Plast Surg. 2006;22(1):9-27.

- Kim DW, Lopez M, Toriumi DM. Revision rhinoplasty. In: Cummings C, ed. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. 4th ed. New York: Mosby Elsevier, 2004.

- Kim DW, Toriumi DM. Nasal analysis in secondary rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2003;11(3).

- Orten SS, Hilger PA. Facial analysis of the rhinoplasty patient. In: Papel ID, ed. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2nd ed. New York; Thieme Medical Publishers Inc; 2002:361-368.

- Park SS. Treatment of the internal nasal valve. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 1999;7:333-346.

- Tardy ME, Kron TK, Younger R, Key M. The cartilaginous pollybeak: etiology, prevention, and treatment. Facial Plast Surg. 1989;6:113-120.

- Tardy ME, Toriumi D. Alar retraction: composite graft correction. Facial Plast Surg. 1989;6:101-107.

- Toriumi DM, Josen J, Weinberger M, Tardy ME. Use of alar batten grafts for correction of nasal valve collapse. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:802-808.

- Toriumi DM. Management of the middle nasal vault. Op Tech Plast Reconst Surg. 1995;2:16-30.

- Toriumi DM. Structure approach in rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2000;8:515-537.