|

Although E. Gaylon McCollough, MD, FACS, is recognized worldwide as a surgeon and teacher, he gives much credit to his own teachers for his success in the plastic surgery field.

He was an Academic All-American offensive center on Alabama college football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant’s 1964 National Championship Team. (As a testament to the coach’s influence, McCollough authored a book about Bryant that was published by Compass Press in 2008.)

In 1964, when McCollough was drafted by the NFL’s Dallas Cowboys, he asked Bryant’s advice on the best course to take. Bryant’s response was, “Can you live without football?” He advised McCollough to put football aside and attend medical school.

“He said that the life of a professional football player was a short one, and that I could practice medicine for the rest of my life,” says McCollough, who reminisces fondly and relaxes amid a hectic work day in his Gulf Shores, Ala, practice.

After taking Bryant’s advice, McCollough notes, he recalls sitting in a 10-by-10-foot apartment with his wife—and a baby on the way—when Sunday-afternoon football came on television. As he watched former teammate Joe Namath and his other buddies playing ball, he felt a twinge of regret. Those slight misgivings, though, were short-lived because just as the careers of those football stars were ending, McCollough’s was just beginning.

“When I see them now, I am thankful I’m in good health and have all my body parts,” he laughs. “No knee replacements, shoulder injuries, or any of that.”

In a career in medicine, McCollough has distinguished himself as a pioneer in his profession. He is included in The Best Doctors in America; has received several academic, professional, and civic awards; is listed in the National Registry of Who’s Who in medicine; is a member or leads or has led many professional associations; and has been awarded the Distinguished Service Award from the United States Sports Academy for contributions in the field of health-enhancement sciences.

PSP: Having been in the field for over 3 decades, how has the way you run your practice changed over time?

McCollough: My practice has not changed a great deal. In the 35-plus years I have been in practice, I have focused on nasal and facial surgery, including surgical skin resurfacing. When I have identified shortcomings in traditional techniques, I have modified them here and there but have not really jumped on the bandwagon with every new device or modification in nasal and facial procedures that have come down the pipe.

I’ve spent my career trying to minimize patient discomfort and shorten healing times, while at the same time create natural-looking results.

I felt from the very beginning that I wanted to be a surgeon and have tried to stay true to my training. I have not become involved in many of the noninvasive or minimally invasive things that many of the plastic surgeons have taken on.

While injectables have their place, they cannot replace surgery. I have steered clear of commercial devices and procedures that have been marketed to the profession.

PSP: Are all the changes occurring in the world of plastic surgery good, or are there some things that should not change?

McCollough: I learned long ago that if you find a few things you are good at, and you do them well and not try to become a jack of all trades, you are more efficient and more proficient in practice. You become known as a specialist in your field, and I think that serves you well as time goes by.

PSP: Are some of the trends in plastic surgery not necessarily for the best?

McCollough: It seems that surgeons are becoming “non-surgeons” and “non-surgeons” are trying to become surgeons. Both are abandoning their core training to compete for cosmetic procedures. I also believe the specialty changed when aesthetic surgery became incorporated in university settings.

Initially, plastic procedures that were performed in universities were reconstructive and traumatic repair in nature. Then universities began to recruit aesthetic surgeons and require them to publish in order [to] climb the career ladder. That’s when things changed, too. A professor would change a traditional procedure, often making it more complicated. Then they would present these papers at national meetings. Attendees would then feel compelled to incorporate these changes into their own practice. What happened was that the requirement for publication has ultimately created confusion and complexities in the field of plastic and cosmetic surgery. In making traditional surgical procedures more complex, results and outcomes were not necessarily enhanced.

Rather than complicating matters, my goal has always been to simplify procedures as much as possible and still obtain optimal results. I have developed algorithms designed to match tried-and-true procedures with the individual needs of patients. In recommending a treatment plan for patients, I use a facial-rejuvenation system that I created, and I recommend procedures that provide long-lasting, natural-looking results. That’s how a surgeon gains a patient’s confidence for the long term and builds-in a word-of-mouth referral base that withstands economic downturns.

|

| McCollough’s respect of traditional aesthetic medicine has made his Alabama-based practice a popular destination. |

PSP: What are some of the newest technologies and procedures that impress you or grab your attention?

McCollough: I am waiting for fat transfer to be worked out, but I’m not sure that we are there yet. I’m really unimpressed by a lot of the new changes in procedures and technologies. All one has to do is to review old textbooks and articles on plastic surgery to see that our predecessors may have already had answers to the questions we seek. In many cases, their results are equal to—if not better than—some being published today using newer technology and more complicated procedures.

There is one thing that came along that revolutionized the field, and that is liposuction. I stayed on the sidelines, so to speak, until a lot of the more senior members in the field worked the bugs out of the system. I was glad I waited because early on there were issues with liposuction, especially in the facial area. The pioneers tended to remove more fat than necessary, leaving behind scarring and skeletonization. There were some problems with some of the cannulas that were used; some bumpiness and lumps in the face that were difficult to correct. We later realized there were some regions to be avoided.

As the procedure became more refined and more predictable, it has given a tremendous advantage to the field—especially to those surgeons who do body work.

In the 1990s, the lasers came along. We were told by the salesmen and physician advocates that lasers were going to take the place of chemical peels and dermabrasions. At that time, I had a clinic in Birmingham. We bought four or five of the latest and greatest lasers, and over the next half-dozen years I stopped doing phenol peels and wire brush dermabrasion, believing what the companies told us—that the lasers would replace those procedures. Try as I may, I never got results as good as those we were able to achieve through the peels and dermabrasions, so I went back to them for skin resurfacing.

Currently, I don’t even own a laser and find that I continue to get better results with the dermabrasions and phenol-based peels. This is going to run contrary to a lot of what you hear because, unfortunately, many of the training centers today are not even teaching the techniques for chemical peels and dermabrasions. Rather, they are teaching only the use of the laser technology. Young doctors are being deprived.

PSP: What is your take on the so-called “turf wars” that continue between core plastic surgeons and the noncore practitioners who have nosed their way into the business? Should they be accommodated, or should they be required to become fully certified prior to calling themselves cosmetic surgeons?

McCollough: This is and has been an ongoing battle. Even in 1974, when I finished my training, it was an issue. It got so bad that the Federal Trade Commission became involved for restraint of trade issues. It was not until a defamation lawsuit was won by specialty plastic surgeons against general plastic surgeons—and a huge penalty slapped on the plastic surgery authors—that the things settled down a bit.

I have a very different perspective than most of the surgeons you will talk to about this. I am a facial plastic surgeon, and I do not waiver from or venture out from that. That is my training and my area of expertise. However, I have had plastic surgeons perform body procedures in my practice for the past 20 years. When they joined me, some had never personally performed some of the facial and nasal procedures for which they had been “certified.” On the other hand, many surgeons who are certified by other boards (like otolaryngology—head and neck surgery) have been superb technicians and very competent to perform these surgeries.

Too much emphasis is put on a framed document, and not enough is put on the hands-on experience and technical skills of the surgeons and practitioners.

Recognize that aesthetic medicine and surgery is changing. Because of decreasing reimbursements from third-party payors, more physicians are being attracted to the field. Some of them have had no prior training. That is creating a lot of problems.

One of the big problems is the commercialization of new techniques and procedures with “trade marking.” Physicians are recruited to perform those trade-named facelifts or cosmetic procedures. Sometimes these doctors are not surgeons or they have had little to no training in plastic surgery. They are taken in and given a 1- or 2-day course on how to do a procedure. They market themselves to the public as experts in the field of plastic surgery. This is part of the confusion that’s being created. There are a lot of doctors from nonsurgical specialties that are beginning to perform one-size-fits-all cosmetic procedures, particularly facial work, lasers, and injectable procedures of all kinds.

I have been in the middle of this issue for a long, long time, having been the president of several organizations whose members offer both cosmetic and reconstructive surgery—facial plastic surgery organizations, head and neck surgery organizations, and cosmetic surgery organizations. I am not new to the certification process. I have taken the exams and given the exams. I was, in fact, elected by my peers as the first president of the American Board of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.

The ENTs, pejoratively referred to sometimes as noncore providers, are actually certified in otolaryngology—head and neck surgery. The residency and board examinations concentrate heavily on plastics. Diplomates might argue that they are more qualified and far more highly trained than some plastic surgeons whose core was in general surgery.

Then there is the 1-year fellowship in facial and nasal plastic surgery. The residency of the plastic surgeon from general surgery is only 2 to 3 years. If they came through general surgery first, they have usually performed little, if any, head and neck surgery. Also, in the 2 years of plastic surgery residency, surgeons must become proficient and certified in five to six areas of plastic surgery: body surgery, hand surgery, burn surgery, cancer surgery, and facial and nasal surgery. That’s a difficult challenge.

A closer comparison of each specialty’s examination criteria would show that 25% of the exam for otolaryngology—head and neck surgery is facial plastic and reconstructive surgery, which is higher than the general plastic surgery certifying exams. And the examination of the American Board of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive is 100% face, nose, head, and neck.

On another front, the American Board of Cosmetic Surgery is also a certifying board that requires training and experience in cosmetic or aesthetic surgery for that certification. Some would lead you to believe it’s a paper mill—you pay your dues, send in the papers, and you become a board-certified cosmetic surgeon. But that is not the case. If you really drill into it, you will find these surgeons are generally qualified to do what they do.

As always, and with any field whether it is a family practice or a surgical specialty, there are always “fringe” people who tend to give others a bad name. When I served as a member of the Alabama Medical Licensure Commission, my colleagues and I had to revoke the licenses of doctors from a variety of specialties.

|

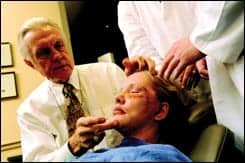

| McCollough focuses on nasal and facial surgery, including surgical skin resurfacing. |

PSP: You do a lot of e-consults?

McCollough: I do at least three to four e-consults per week. These are generally individuals who call after hearing about us from a friend or seeing our Web site; or, they have been referred to us by someone else but they live far away. Some are local, but most are from farther away.

PSP: How does it work?

McCollough: Generally, these people call looking for information. We first direct them to my Web site, where there is an entire consumer information book available online. There are also before-and-after pictures that demonstrate my approach to facial and nasal plastic surgery, anesthesia information, and postop care information designed to assist them in wound care and healing. After that, we invite them to send or e-mail pictures and set up a conference call. Sometimes we do a Skype interview, so we can see each other face to face.

During this preliminary consult, I give them a general impression or overview of procedures to consider. We discuss what the priorities are and give some quotes based on the procedures we discuss. I stress that I can’t recommend a final plan until I see them face-to-face. Next, we schedule a tentative date to see them preoperatively, in person. It is at this meeting that plans are finalized—this is the official consult and decision-making time.

PSP: How much online technology do you use to acquire or grow your patient base?

McCollough: We haven’t done a lot with Facebook or Twitter or any of those areas yet, although there are a lot of people encouraging me to do so. We mostly rely on the Web site, and more recently on the Skype technology. I think this will be very important for the future, though one has to be careful not to violate laws that govern practicing across state lines.

PSP: For the plastic surgeon just coming into the field, what advice would you offer on how to build a successful and profitable practice during the economic recession?

McCollough: A lot of the new plastic surgeons are being trained with device-based technology rather than the older techniques that are tried and true. Regardless of one’s core training, it is tempting to incorporate all the available techniques and technologies into your practice, but I would advise against that.

I think it is unwise to try to be all things to all people. Don’t be a jack of all trades, but be an expert at what you do. What a plastic surgeon or a facial surgeon goes through to earn the title of surgeon is something to be very proud of. When you begin to dilute your surgical expertise by offering the same kinds of things that nonsurgical fields offer, you become something different. You are now competing with non-surgeons and dilute the argument that we are surgical specialists. To avoid this, choose two or three procedures you really like and become the best in your field. You will be recognized as the expert on those procedures by your peers and the public alike.

Be slow to embrace so-called new technology. Give it time to be tried and tested by more experienced surgeons before you take it on. This will make your practice more successful and keep your overhead under control. If you go back and look 5 to 7 years at what the latest and greatest technology or technique was then, and see what is still around versus what has gone by the wayside, you will have a good indicator of what works and what doesn’t.

A good rule of thumb is to wait 5 to 7 years on a new technology before you embrace it. My rule is not to be the first or the last to take on a new technology, so that you don’t invest too quickly in something that in 2 years you find was a waste of your time and money.

Learn early in your career that it is not necessary to have every piece of equipment available or incorporate unproven procedures and technology in your practice. Recognize that the companies that produce these newest technologies control our activities a lot by advertising and drawing people in. The good thing is that I have found that patients will usually listen when you tell them that what they may be asking for isn’t necessarily what they need; or that there are better, more long-lasting alternatives.

PSP: Has the economic decline brought about a decline in revenue or procedures performed in your practice?

McCollough: Anyone who is being honest will admit that there has been a decline in revenue and patients and procedures with this latest economic decline. The key to continuing to be successful in practice is doing the bigger-ticket items rather than lots of less effective procedures, like the injectable therapies and such. In doing procedures or techniques that are tried and proven effective, credibility is built and maintained in the practice.

Earn a patient’s trust with the little things, and big things will follow … for a very long time. The economic decline may be more or less for some based on geographical location, however. The fact that my patient base is “worldwide” in nature has really helped me during every economic downturn over the past 35 years.

PSP: Do you believe we are making “much ado about nothing” in our concerns over the economy and pending changes? Are we seeing a natural economic cycle play out?

McCollough: This is a real recession. I don’t think anyone knows when we will come out of it. However, I have been through at least four of these economic recessions, and although this one is a little deeper than the others, it is no time to panic. This, too, is a part of the ebb and flow of the business.

There has probably been about a 15% to 25% decline in the requests for aesthetic surgeries at this time, but the patients are not going away. The problems that bother them will only mount as the years pass. Though their timing might be delayed, their plans for surgery are not going away. My advice to my colleagues is to stay the course through the recession. Don’t lose the focus on surgery. On the heels of every recession, there has been a boom in plastic surgery. I would advise the younger doctors to stay true to themselves and their profession, and not be lured away by anything that sounds too good to be true.

PSP: How do you feel President Obama’s health care reforms will impact your practice or that of plastic and cosmetic surgeons in general?

McCollough: It won’t make a lot of difference to the aesthetic arena simply because basically 100% is paid by the patient at or before the time of the procedure. In my practice, we don’t deal with the insurance companies and, by choice, I am not a Medicare provider and don’t take [Blue Cross Blue Shield] or any third-party payor. The patient pays, we file the claim, and if the surgery has a legitimate functional or reconstructive element then whatever the insurance company pays is paid directly to the patient. Other than filling out the claims as a courtesy to the patients, we are not involved in the reimbursement loop.

However, I do believe that government-run health care will adversely affect the mixed providers—those of a reconstructive or functional nature.

PSP: What do you believe is the secret of your success?

McCollough: My advice is for anyone. When you are considering who you are going to marry and spend the rest of your life with, be sure that your goals and aspirations are the same. Be sure that you like and respect each other. I have been married since 1965, and my wife has been the greatest partner and right there beside me the whole time, especially during the early years when adversaries were using ruthless measures to try and damage my credibility and reputation. She has rolled up her sleeves many times when we have needed to expand a clinic or build a new house.

Your home life can make or break your professional life, and I have been extremely fortunate to have my wife. She has been a wonderful partner throughout the whole process, and she deserves a lot of the credit for my success. In fact, she has been to so many plastic surgery lectures she could give as good an interview on it as I can. She is as passionate about it as I am.

Connie Jennings is a contributing writer for PSP. She can be reached at [email protected].

A SOLID FOUNDATION

|

A very important aspect of E. Gaylon McCollough’s success can be attributed to his parents. Although neither of them even completed high school, McCollough says, they always encouraged him to excel. They gave him every opportunity and always desired more for him than they had. They wanted him to have the education they never got, he notes, taught him good work ethics and how to work hard from the beginning—selling peanuts on the streets of his hometown as a 6-year-old and, later as an older boy maintaining a newspaper route. It was a background of being urged to take personal responsibility and receiving encouragement from loving parents.

Flash-forward to the early 1990s, when McCollough thought he might retire. He had sold his Birmingham, Ala, clinic to a national medical corporation, dropped to a 2-and-a-half day workweek, played lots of golf, read books, went on a lot of trips, and saw a lot of movies.

“I realized, however, within about 6 months that my happiest days were those he spent at work, caring for patients, and performing surgery,” he says. In response, McCollough found a place he would like to live out the rest of his days, moved there, and opened his current practice.

Clearly, he isn’t ready to retire. Jokingly, he advises his staff that if he begins losing his way to work, they can retire him. Keep in mind it takes McCollough only a minute-and-a-half and two right turns from his house to his clinic

Not only does he manage the McCollough Institute for Appearance & Health, in Gulf Shores, Ala, but he also has time to raise Tennessee Walkers and Racking horses. He raises and breeds these horses with a passion.

In addition, McCollough is the author of several books, including The Long Shadow of Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant (Compass Press; 2008), Let Us Make Man (with Carrie White and Charles Billich (Compass Press; 2007), and Shoulders of Giants: A Facial Surgeon’s Prescriptions for Life’s Dilemmas (Albright & Company; 1986). “Writing is my avocation,” he says.

Presently, he is working on a new book: “A novel about a doctor who, through a series of unprecedented events, becomes president of the United States,” he says.

Finally, strict scheduling during his working day allows McCollough to spend time with his grandchildren almost daily—”The ones who live close, that is,” he says. His daughter has a degree in psychology, and his son is an architect.

—CJ