|

In December 2008, medical history was made in the United States when the first-ever partial face transplantation—a near total face transplant—was performed at the renowned Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. The focus of the operation, Connie Culp, was mutilated years earlier by a shotgun blast to the face. The outcome of the surgery has given her a bright new hope for the future, and put the surgeons involved in the spotlight.

The team that performed the 22-hour face transplant procedure consisted of eight surgeons, which included seven general plastic surgeons and the primary Microvascular surgeon, Daniel Alam, MD.

Alam is a facial plastic surgeon and head of the Section of Facial Aesthetic and Reconstructive Surgery in the Head and Neck Institute at the Cleveland Clinic. In addition, Alam has been in practice for 8 years and is dual boarded, by both the American Board of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and the American Board of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery.

BACKGROUND

In August 2008, Alam’s colleague, Maria Siemionow, MD, PhD, DSc, the primary investigator of the Face Transplant Research Protocol, asked him to write the specific operative plan for the surgery of a patient who was missing her midface.

By September 2008, Alam had created the 35-page step-by-step instruction manual of how to do a transplant on this patient. As Alam explains, “Maria had done the legwork, got the board approvals, and was the driving force behind the project. I was asked to plan and detail the specific surgery of the patient because of my expertise in facial plastic surgery. I authored this protocol, and then in December we did the surgery.”

The patient’s original injury was a shotgun wound to the face. The then-40-year-old woman was injured in an attempted murder-suicide in 2004. Both she and her estranged husband, the shooter, survived. He is serving a 7-year sentence for the crime. She was left with the middle of her face blown off, and has had to endure two dozen ineffective reconstructive surgeries over the past 5 years in an attempt to rebuild her face. The protocol for facial transplantation at the Cleveland Clinic was considered a last-resort surgery for her, Alam says.

Earlier this year, Alam cowrote the article, “The Technical and Anatomical Aspects of the World’s First Near-Total Human Face and Maxilla Transplant,” which was published in the November/December 2009 issue of the Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. It was also highlighted in an editorial in the November 15, 2009, issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association. PSP recently discussed this unprecedented case and the ramifications of this experimental procedure with Alam.

In Part One of a two-part series of articles, Alam reviews the events that led up to the surgery, including a discussion of donor selection and preparing the patient emotionally for the procedure. The second part of this interview will be published in the February 2010 issue of PSP.

PSP: What did the procedure entail? What did you transplant?

Alam: Facial transplantation is a technique where instead of using parts of a person’s own body—where traditional reconstruction is involved using flaps and grafts—we actually transplant from a donor portions of tissue and components of the face.

At this stage, it is experimental surgery, so the use in patients is isolated to people within a defined experimental protocol. In the case of our patient, Connie, her injuries included a complete absence of the middle of her facial structures. She was missing her nose, upper lip, palate, and teeth. Basically, most of the bone structure in the middle of her face, as well as the muscles and nerves in the area, were destroyed or lost in the injury.

Based on that defect, we planned our model of the potential allograft from the donor. We spent a lot of time in the lab with the cadavers, and mapped out the specific flap procedure that would allow all of those parts to interlock and to be replaced. Instead of trying to build from scratch from spare parts from a given person, transplantation allows you to replace all of the parts from a donor in one defined procedure.

|

In December 2008, Connie underwent the procedure. She had all of these structures replaced from a beating-heart donor individual where the face was procured and transplanted. We took the blood vessels, nerves, muscles, bones, and skin, everything to integrate into Connie’s face so that now over time this will become her face.

There were a total of eight doctors who were there. One team was in Connie’s room, most of the members of which had operated on her before and were familiar with the nonviable tissue and the hardware in her. They worked for 10 hours to clean her up and prep her for the new face.

I was involved in the harvest side. That procedure took my team and I 8 hours. We did these surgeries simultaneously and in adjacent rooms. When the recipient room was ready, I brought the face over and then did the micro portion of the case to restore the blood supply to the donor face. We then began the multilayer inset process, connecting and suturing the inside lining of the mouth, the nerves, the muscles, the skin, the sinuses. The whole procedure took 22 hours. By the time we finished that operation, it was mid-afternoon the next day.

PSP: Was her procedure complete at the end of the transplant?

Alam: There are a few stages. The first is obviously the major transplant procedure, but even that is staged. When the operative plan was written, we had a component of it to include for the extra tissue that remains—so, it’s a staged procedure.

At the initial stage, the blood supply is restored—the face is in essence “brought back to life” on the new recipient, but this is only the first part of its recovery.

To achieve the long-term goal, the face would have to move and feel … to smile, making use of the muscles and nerves, developing sensation and movement. This part of the procedure is akin to planting a tree and waiting for it to grow. We basically sew the nerves together, sew the tissues together, and allow the nerve endings to grow from the recipient into the donor face. It’s kind of one of these fascinating tissue integration things where it’s actually Connie’s facial nerves that are growing into her donor flap, and then will make the donor flap move. We’re connecting into Connie’s brain through these nerves into her new face. That second part is what takes time. Nerves like this typically grow about a millimeter a day, so you’re talking about 6 months to a year before we start to see anything astonishing.

PSP: Is there a transfer of identity with facial transplantation?

Alam: We transplant the entire face as a block—the bone, the skin, the muscle, the nerves. It is moved as a unit. That’s what makes it a one-step procedure. Every piece that is missing gets mapped out, almost like a jigsaw puzzle.

Our face is a combination of all structures, deep and superficial. When you actually transplant the face like we did with Connie, not the whole face, but just part of it, the components become the hybrid. You don’t look like what you used to look like, but you also don’t look like the donor. It’s a changing paradigm in the way plastic surgeons typically view reconstruction. If you had a terrible injury, typically my goal would be to make you look exactly like what you used to look like. This is sort of like throwing in the towel on that concept—the wounds are so severe that we are going to make you look like someone else but not necessarily like the donor. There is not an identity transfer here, but more accurately an identity transformation.

Connie said it better than anyone before the surgery. She said, “At the way I am right now, I don’t look like a human being. I don’t have the ability to be attractive as a human being. People don’t view me that way.”

We are doing a procedure like this to give her the ability then to reintegrate into society, to regain the bare minimum of humanity needed for social interaction. Much of our existence is based on social interaction. Maybe we don’t see people like this on the streets because they never leave the home.

|

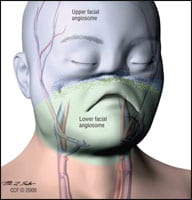

| Figure 2. Preoperative facial angiosomes. Due to the complete absence of midface vascularity and prior recipient vessel depletion, the recipient face had essentially become two isolated angiosomes. The upper angiosome supplied by bilateral distal external carotids is shown in blue, and the lower angiosome supplied by the left facial artery primarily is shown in green. (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2009. All Rights Reserved.) |

PSP: Medically, what will this surgery do for her? Will she be able to eat, and breathe from her mouth and/or nose?

Alam: Before the surgery, she required a tracheotomy; she no longer requires it. Before the surgery, she had no nose; she had no breathing structure; she had no palate. She had difficult breathing, difficulty eating, difficulty making sounds, and speech patterns were very broken. Because she had no nose and no airway, she needed a trach to breathe and also she had a G-T tube for nutrition.

By virtue of recreating her nose, she is now also able to smell. The structures enabling her to smell [were] never injured—they were only blocked. People always seem so impressed with that, but actually by giving her a nose we only gave her a conduit for air to get back her native sense of smell. From her standpoint, we gave her back her sense of smell.

PSP: As far as what your team gave her, with what in particular were you most impressed?

Alam: This is where you learn where your limitations are. What was amazing to me was when I detached the face from the donor patient and all of the blood drained out of it and it instantaneously became this cadaveric, lifeless entity, and it was so dramatic. I have never had such a dramatic moment in my career, to watch this happen within seconds. It was by far one of the most humbling moments in my career. I looked at it and thought, “My God. Is it ever going to come back to life?” It just lost all sense of life in it.

Walking into the other room and beginning to sew the blood vessels together, I felt a sense of doubt in that situation. When I released the vessel clamps and it came back to life on Connie, it was like being present at a miraculous transformation. The most impressive thing to me was just being witness to that, actually being a participant.

PSP: What is Connie most impressed with?

Alam: From her standpoint, we went through this whole process with ethics boards and other people trying to rationalize the importance of functional improvement—the ability to talk better, the ability to eat better, the ability to do these things better. But Connie will clearly reiterate that it was the aesthetics that were really important for her. And I think people make the mistake in thinking that aesthetics are really about vanity. Yes, if you are 18 and you’re a pretty girl and you want the bump off your nose, then that’s a lesson in vanity as a plastic surgeon. But there are situations where your aesthetics are so compromised that you have lost your sense of being a human being.

|

See also “The Honorable Surgeon” by Connie Jennings in the October 2009 issue of PSP. |

|

For all of us, there is an incredible drive to be social creatures. It is that piece that is the most important to her. She looks at being able to be in a public setting and not have people be afraid of her. And she would trade the improvement in speech and increased sense of articulation and smell for that. We like to talk about these things because we like to think that this is a medically and functionally important procedure, but truly for the patient it is the other factor, as well.

PSP: Who is the donor in a case like this?

Alam: Most donors are beating-heart donors who are clinically brain dead. There is no cerebral brain activity whatsoever. It is a patient in the ICU on a respirator until the family decides it is going to donate organs.

With the face case, it is a specific protocol [in which], after all of the other organ donor discussion is done, we have a specific specialist who goes in with the family and discusses all of the issues related to the face; and then they have the option to decide whether they want to donate the face or not. We did not want to interfere with the other organ donation process at all. Our organ donor donated other organs, as well.

For this case, we asked for same sex and within 20-year age range of the patient, and some basic criterion. She is not completely immunologically cross-matched, but that occurs in other types of transplants so there was nothing unusual about this case.

Amy Di Leo is a contributing writer to PSP. She can be reached at .

Part two of this two-part series will be published in the February 2010 issue of PSP.