|

Now does Rudi Unterthiner, MD, FICS, quantify a spiritual and physical odyssey that has taken him both around the planet and deep inside his soul? It has been a journey from the inner circle of Hollywood—in which the biggest stars became personal friends as his practice grew in the 1970s and ’80s—to running a free clinic serving the needs of a desperately poor Baja California-based population…and beyond.

In the process, he has arrived at answers to questions that have troubled, informed, and directed him in his journey. Some of these questions relate to the art and business of plastic surgery.

Ultimately, much of his additional soul-searching was brought to the surface during the writing of his acclaimed 2008 novel, Faces, Souls, and Painted Crows (Chronicler Publishing), in which his thinly fictionalized protagonist, Dr Paul Reiter, discovers a world beyond the confines of plastic surgery. In a review of Faces, Souls, and Painted Crows, the Midwest Book Review aptly describes Reiter as someone who “is caught between the forces of his life that push him to work for wealthy Hollywood, and his true calling to help the Indians of Mexico’s Baja. Ultimately his Indian wife is the one who shows him insights into the connections between a person’s face and their soul.”

Although his business card provides an address for his private practice in Rancho Mirage, Calif, Unterthiner spends most of his time on Quadra Island, off the eastern coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, and part of the Discovery Islands. He is not active in his practice but continues to follow and comment on the industry.

First, though, the questions and answers. When I met Unterthiner at a book signing, he immediately impressed me with an answer to my own question, “What is the morality behind plastic surgery?” His responses went beyond the usual clichés that I hear from almost every practitioner I ask—It is not just about the satisfaction a physician gets from helping patients gain improved self-esteem through plastic surgery, he says.

“To begin with, morality has various definitions,” he says. “I think that anything taken to excess deviates from its inherent ‘goodness’ and can become immoral. That standard can be applied to money, alcohol, food, sex, and yes, even plastic surgery.”

In Unterthiner’s novel, one of the characters, an Indian hermit who lives on Mexico’s Sea of Cortez, paints wild crows and makes the point that “a little color” on the wings of the birds can make them happy, while too much makes them garish, grotesque, and unhappy.

“It all equates with excess, which I see as a deviation from morality,” he notes.

Originally, he says, plastic surgery was performed for the reconstruction and repair of congenital deformities, traumatic injuries, and removing cancerous tissue.

“Perhaps one of the reasons I ended up doing cosmetic surgery was because of the reality of medical economics in the United States,” he continues. “At the beginning of my practice, I brought out that point during a medical staff meeting. I expressed dismay that our services were not accessible to those with no insurance or money, and I wondered about adopting a more equitable system. My remarks were not well taken, and I experienced ‘political’ challenges in mainstream medicine after that.

“In most industrialized countries, medical care is a universal right and is available to all, regardless of financial status. Trying to practice in the US, I couldn’t turn away people who needed help merely because they didn’t have the means to pay for it.

As an example, a young girl came to me several days after her horse had literally bitten a part of her lip off. She’d been to emergency rooms and a number of surgeons, but no one was willing to help her because she didn’t have medical insurance or money. We were able to restore her lip using the facilities of my private clinic, and I was happy to do it without charge. Still, it was impractical to run a totally pro bono practice, and I found charging for cosmetic surgery ‘morally easier.’ After all, many aesthetic surgeries are like a Rolls Royce—a luxury. A cut tendon in a hand or a cleft lip in a child, on the other hand, should be a basic need that is met by a civilized society.”

ADVICE FOR THE YOUNG AT HEART

What would Unterthiner say to a young person entering the aesthetic medicine field today?

“Number one, noli nocere—do no harm,” he says. “Two, never forget the overall picture. You are just a human being. You are a physician trained to treat all manner of ailments. You are lastly a specialist in the field of plastic surgery.”

In practical terms, these principles guided him 40 years ago and up to and including today. “And even then there were times when I too felt frightened by the prospect of opening a practice,” he says. “The environment today is different because there are so many more people practicing this specialty—even those not particularly trained for it—and the competition for a limited ‘market’ is greater. That said, I believe it is more important than ever to remember the principles that motivated you to become physicians in the first place, and those upon which the specialty was originally founded.”

In Unterthiner’s novel, the protagonist is assailed by a nagging doubt of whether or not it is morally justified to do moderately invasive procedures for the sake of “beauty.” In an attempt to mollify this all-consuming preoccupation, he ultimately decides that to justify aesthetic surgery he has to be reasonably certain of noli nocere.

During his medical training at the University of Alberta, Unterthiner recalls that the college’s dean, Walter McKenzie, who was also president of the American College of Surgeons, always made a point that he was a physician first and a surgeon second. “The medical school had a basic philosophy—to give everyone a wide medical education and graduate physicians who were grounded in the basic sciences and general medicine,” he recalls. “I have the impression that the training now is more streamlined toward an early emphasis on specialization. Just last week, as a matter of fact, I had a guest who is the head of the Department of Head and Neck Surgery at a prestigious American University. When he saw me treat general medical problems in the local Indian community, he said, ‘I couldn’t practice medicine like you. All I know about treating patients is the oral cavity.’ “

|

| In honor of ancestral rituals, a totem pole was raised on Unterthiner’s Quadra Island property in 2009. |

BEAUTY AND THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

At the beginning of his career, Unterthiner struggled with the perplexing dilemma of justifying fairly invasive surgery merely for the sake of aesthetics. “In the end, I assuaged my conscience by coming up with a compromise based on the assumption that no one can be a master of all trades and that whatever I did in the field of aesthetics would have to be safe, have reasonably predictable results, and not deviate drastically from nature,” he says.

He decided the only way he could adhere to that premise was to concentrate on a small number of procedures; that is, facelifts and blepharoplasties. “Even at that, it took time to refine my practice,” he says. “I remember doing a facelift in the early days of my career on a 72-year-old, wrinkled lady with a 90-year-old body. The end result was a face that was fresher but didn’t fit her cadaver-like body. It made her look almost grotesque, and I realized I needed to be more discerning.

“There’s an old saying, ‘Beauty is in the eye of the beholder,’ which translates to the reality that when we’re dealing with women, or men for that matter, we deal with individuals whose concept of beauty encompasses a wide range,” he adds. “Some have reasonable expectations to look fresher, but what about 70-year-olds [who] want to look like thirtysomethings? I have the impression that this is an age-old problem and not limited to plastic surgery.”

What were the most difficult cases that he treated? “Some of the most challenging were reconstructive cases that involved more than one procedure and surgeons from different specialties,” he says. “Congenital deformities of the chest, like pectus excavatum, uro-genital problems, spinal cord anomalies, and craniofacial deformities, rank as the more difficult procedures.”

THEN AND NOW

In comparing plastic surgery of over 30 years ago to current standards and practices, Unterthiner is quick to point out the new complexities facing physicians who are entering the field.

“In the early ’60s and ’70s, people who had not gone through the formal training—normally 4 years of general surgery and 2 to 3 years of reconstructive surgery—were not part of the specialty,” he says. “One of the most striking differences now, of course, is that physicians and surgeons who have not trained in the field—dermatologists, gynecologists, general surgeons, and even dentists—are calling themselves cosmetic surgeons. There is even a Board of Cosmetic Surgery, which has totally different standards than the Board of Plastic Surgery.

“I have no quarrel with the fact that in the late ’70s, ENT specialists through their training in facial surgery became part of our specialty. Nevertheless, I did wonder about some of them billing themselves as experts in breast surgery and liposuction of the lower limbs and groin areas. While I do believe that some of these people may have a natural talent to do some of these procedures, it does not negate the effect of unqualified physicians entering the field because of monetary rewards. The inherent risk to patients is unfortunately much greater.”

Unterthiner invokes the name of JJ Longacre, MD, who was his mentor and a pioneer in the field of plastic surgery, as well as a founding member of the American Society of Plastic Surgery and the American Board of Plastic Surgery. “Initially, he was a general surgeon who went on to train in England during [World War II], where work was done on returning soldiers burned or disfigured in battle,” Unterthiner says. “Upon his return to the United States, he also developed a world-famous aesthetic surgical practice, and used the proceeds of that practice to fund and make possible the many cases he did without charge for children with congenital deformities, trauma, and cancer. I do recall clearly the many operations we did, and he always made a point that it was more satisfying to him than to do something like pectus excavatum, a good facelift, or breast reduction.

|

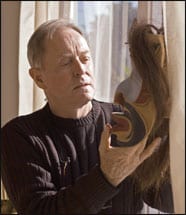

| Unterthiner believes that Native American culture has much to offer many aspects of modern life. |

“As far as sophistication and improvement, it seems that development of new technical and surgical advances in aesthetic surgery outpaces by far such advances in reconstructive procedures. It does make me wonder about the motive and the emphasis.”

Despite some concerns about the changing face of plastic surgery and the qualifications of those entering the field, Unterthiner believes North America has by far the best medical education system in the world.

“Many medical schools in Europe and South America and the Far East have no numerous clausus and admit thousands of students to their faculties,” he says. In 1985, he wanted to do surgery in Europe, and in order to get a medical license there he needed a medical degree. To accomplish this, he enrolled in a medical school in Italy and repeated the final year of studies.

“I remember the lecture halls of that university being packed with hundreds of students who didn’t even regularly attend classes,” he continues. “What they basically needed to graduate was the signature of a clerk affirming that they attended lectures from time to time.

“I wrote a thesis on the influenza virus vaccine and eventually obtained a medical degree as a 50-year-old board-certified surgeon from California. It was obvious to me during that experience that the intensity of my training in North America was very much more rigorous, with small classes and a great emphasis on practical experience, from delivering babies to assisting in surgery. The training that I noticed in Italy was largely theoretical, with little or no practical experience. I encountered plastic surgeons, for example, who were qualified as [being] board-certified but had never touched a scalpel.”

ENTERING THE THIRD WORLD

Back to the questions that greet the inquisitive interviewer and interview subject alike when attempting to delve into one man’s spirit. What events or situations pushed Unterthiner to embrace the concerns of the people in the Third World?

“There was always a part of me that was drawn to the plight of the downtrodden, the maimed, and the helpless,” he says. “It was in so much of which I saw in the final days of the Second World War.”

In the early 1970s, he began regular treks to Puertocitos in Baja California and soon afterward opened a free clinic.

“I was assailed by that part of me that was attracted to the helpless and needy, and I decided at that time to do what I couldn’t do in World War II—that is, to help the sick and injured who had no doctor available,” he says.

Unterthiner began flying medical supplies on each visit and established predictable routines with another American expatriate. The clinics eventually drew from a large portion of the nomadic Indian fishermen who followed the schools of fish on the Baja coast of the Sea of Cortez.

“While I can’t speak for every surgeon who’s involved in this type of work, I think it’s safe to say that the money can’t match the satisfaction that comes from helping someone who would otherwise be sentenced to a life of disfigurement and disability,” he adds.

Throughout many years of his life as a medical student, physician, and husband, Unterthiner has been influenced by the ways of the Native American. “To begin with, I’ve been married to an American Indian for 45 years who late in life embraced the culture that she was denied for many years,” he says. “I’ve learned a great deal about their belief system, which is based on the connection between the spirit of man and all of nature. In all my relations, be they stone, plant, sea, sky, or animal, each day starts with gratitude and thanksgiving.”

Unterthiner believes that Native American culture has much to offer many aspects of modern life via a celebration of nature. In this belief system, nothing artificial is valued, he says, which would seem a valuable premise also for plastic surgery procedures.

IT’S STILL A BUSINESS

In addition to deeply held philosophical views toward plastic surgery, Unterthiner applied the principles of business and entrepreneurship to his practice. On this score, he confesses that he had an extremely difficult time with the concept of advertising and marketing surgery as a product.

“As physicians with a great deal of education and training, we are not meant to hawk our wares like car dealers,” he says. “In some ways, it diminishes the original objective of our profession—that is, to listen patiently and identify the problem before healing, repairing, or reconstructing. In other words, it’s that special, initial interchange between physician and patient that I hope I never overlooked.”

As an example of what he finds disturbing, Unterthiner brings up the notion of plastic and cosmetic surgeons using computer imaging as a marketing gimmick. “The computer fails to take into account the fourth dimension of time in the healing process,” he explains. “Patients are shown idealized images of what they could look like, but the variables—such as unique bone and tissue structures as well as differences in healing due to various vascularity patterns and the unpredictable effects of scar contracture—are not taken into account. Neither is the skill and experience of the surgeon.”

What does the future hold for plastic surgery in terms of clinical and spiritual potentialities?

“I had the great honor to be the keynote speaker at the end of a meeting of the European Society of Plastic and Aesthetic Surgery a couple of years ago,” he says. “At the conclusion of 3 to 4 days of lengthy scientific papers on surgical techniques, I took the liberty during my speech to approach the field from a spiritual, philosophical perspective. I went to great length, as an older—maybe a ‘has-been’ surgeon—to explain that I felt uncomfortable with the numerous ‘cosmetic surgery shops’ on every street corner in North America run by ‘board-certified cosmetic surgeons’ from dermatologists to internists to dentists, who advertise widely in the media almost hawking their services and promising eternal happiness by being more beautiful. I also told them of my concerns about some of the results that I’ve seen—expressionless people with shiny, pale faces without a hint of wrinkles who look like they’ve been stamped out by the same cookie cutter.

|

See also “Ethnic Rhinoplasty Pearls” by David W. Kim, MD, FACS, in the October 2009 issue of PSP. |

|

“I ended my remarks by recalling how a few weeks earlier I had been in a sweat lodge with the chief of a [British Columbia] Indian tribe. I told him that as an older, retired plastic surgeon I had been invited to address a plastic surgery conference and that I felt inadequate, not quite sure that I was the right person for the task. I recounted how the Chief, after reflecting a long time, told me to not hesitate to do and say what’s right, and that I should take the opportunity to bring the greetings of his tribe and tell the doctors [the following] things: To respect nature and not deviate from it. Remind them that we are all related—Mi Tokyo Oyaisen. To tell them, he said, ‘to be careful about changing someone’s exterior because it could hinder their soul. In our ways we do it different.’ To emphasize his point, I put on an Indian mask he’d loaned me. ‘We just use a mask,’ he said, ‘to smile or look angry when we want to make a point, but when the point is made we take off the mask.’ “

Finally, Unterthiner told those gathered at the meeting “not to take themselves too seriously.”

After the presentation, Unterthiner was “flattered and frankly emotional when several young surgeons came up to my wife and me and said that after days of technical and scientific papers, it was most refreshing and appropriate to be reminded of the spiritual part of our profession.”

Jeffrey Frentzen is the editor of PSP. He can be reached at .

|

THE ROAD TO SUCCESS

Born in 1938, Rudi Unterthiner, MD, FICS, was raised in the Italian Tirol village of Sterling (once a part of Austria) and eventually made his way to the United States in the 1950s.

Although he had no family in the United States and received no financial help from his family in Europe, Unterthiner worked hard to obtain a medical education in America.

As a child, he had seen the many injured and wounded in World War II—one of a handful of pivotal experiences that eventually took him into the medical profession.

“My grandfather also had something to do with this, even though he may not have known it,” Unterthiner stated in an interview in 1978.1 His grandfather had been wounded in the war. “He also was a wood carver, as most people in our area were—when he wasn’t working in the coal mines. Sometimes, I liken plastic surgery to wood curving—shaping things. Don’t forget plastic surgery comes from the ancient Greek word ‘plastikos,’ or ‘capable of being molded.’ “

Unterthiner left Italy in 1957 to escape the Italian army draft. “My people, the Tiroleans, were fiercely opposed to the Italian government’s intrusion on our culture, and I did not want to serve in their army,” he says.

He “escaped” to Austria, where he worked the night shift in a coal mine for 1 year and simultaneously applied for a Fulbright Scholarship to the United States. The scholarship, which allowed him to attend Carelton College in Minnesota, came with a 1-year exchange student’s visa.

“At the end of that year at Carelton, I couldn’t really return to Italy because I was a deserter,” he recalls. “Remaining in the United States meant I had to go ‘underground’ and literally become a drifter, an ‘illegal alien.’ The only work I was able to obtain had to be paid under the table—ski instructor, laborer, drill rigger in Colorado, etc.”

Unterthiner was fortunate enough to be accepted by the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Alberta, which was “a school I could attend as a foreigner and where the tuition wasn’t prohibitive,” he adds.

During summer break he worked as a crop duster and a medical assistant. During this period, he met half-Ute-Shoshone Indian and future wife, Linda. They were married 6 months later and eventually had 3 children. A stint in the Air Force Reserve guaranteed his newfound status as a US citizen.

Following graduation in 1967, he completed his internship at the University of British Columbia and residency work in Southern California. He considered following a career in neurosurgery but was distressed by seeing the numerous horrible brain damage cases caused by accidents. At one point, he assisted in saving the hands and finger of a small boy injured in a lawn mower accident. “I knew immediately I had found my specialty,” he says.

After completing training in plastic and reconstructive surgery at the University of Cincinnati in 1963, the Unterthiners moved to California. “I just wasn’t cut out for the Midwest,” he says. “I loved the multiculturality of California, along with the mountains, the lakes, the ocean, and the desert.”

After starting a practice in Lancaster, Calif, Unterthiner soon found himself in demand from the Hollywood show biz crowd and opened an office in Palm Springs, with weekly trips to Beverly Hills to perform surgery on movie stars. Although these entertainment business connections propelled his career forward, he was drawn to Baja California, where he eventually opened a free clinic and helped those who were much less fortunate.

Unterthiner’s remarkable success story was later read into the US Congressional Record on July 26, 1984, by Guy Vander Jagt, who was a Republican member of the US House of Representatives from Michigan. Vander Jagt said, “At a time when pride and honor in our country is at a renewed height, one can better appreciate the contributions of the Unterthiners of this country to that wonderful and needed spirit.”

-JF

REFERENCE

- Pinkerman J. Rudi Unterthiner…A Human Being, Doctor, and a Plastic Surgeon. Palms to Pines magazine. 1978 (out of print).