cover story | PSP December 2013

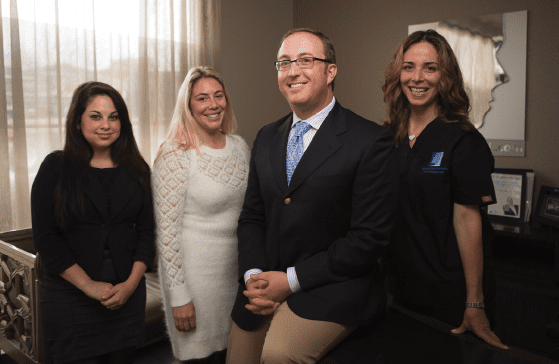

Jeffrey Spiegel, MD, and the dawn of the transgender movement

By Denise Mann

When Jeffrey Spiegel, MD, performed his first facial feminization surgery in 1995, he could not have imagined that treating transgender patients would change how he performs aging-face surgery and result in the “biggest paradigm shift in facial cosmetic surgery within 500 years.”

At the time, Spiegel, the chief of the Division of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Boston University Medical Center, also could not have predicted just how far the transgender awareness and acceptance movement would come in less than 2 decades, or just how big a part of his practice these patients would become. He now gets more than two dozen inquiries and performs at least four facial feminization or masculinization procedures a week. “It is only limited by schedule and not by demand. There are only so many hours I can work,” he says.

And the number of requests is likely to increase even further for both Spiegel and other plastic surgeons with such experience due to societal and political changes that are paving the way toward gender and transgender equality. For example, a growing number of insurers now cover the costs associated with gender reassignment surgeries, and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the US Department of Justice have pursued cases against companies who have discriminated against transgender employees. On the pop culture front, Carmen Carrera is poised to be the first transgender Victoria’s Secret model, and Chaz Bono, the transgender son of Sonny and Cher, gave the other contestants on ABC’s hot show Dancing with the Stars a run for the coveted Mirror Ball trophy.

While no precise figures exist, the National Center for Transgender Equality estimates that between ¼% and 1% of the population are transsexual. “Transgender” is the term used for people whose gender identity or expression differs from their assigned sex at birth. The only recognized and effective treatment is gender reassignment surgery, including facial changes.

When Spiegel first looked, the literature on how to best treat these patients was scant. Now, a Medline search reveals 46 pages of epidemiological and clinical articles on understanding and treating the transgender patient—many of which Spiegel authored, and many more where his pioneering work is referenced.

REVOLUTION WITHIN A REVOLUTION

It is this experience that led to his simple, yet profound epiphany about the aging female face. “As women get older they look more masculine, so all of the anti-aging surgery is really facial feminization,” he explains. “We often see women who are not beautiful, but aren’t unattractive. They are just not gorgeous. When we think about what to offer them, you may think, ‘Well, they don’t need a facelift, rhinoplasty, or their lips made fuller. What do they need?’ They need to look more feminine.”

He now seeks to identify and correct the features that are non-gender confirming, or non-gender enhancing—as opposed to trying to just fit faces to the ratios and proposed measurements that are thought to represent objective beauty.

According to Spiegel’s research, among the most important, but often overlooked, areas are the orbital rims, glabellar bone, and eyebrows—which are the features that we first look at to identify a person’s gender. This paradigm shift in thinking has resulted in a large number of non-transgendered women seeking Spiegel out for aging face and cosmetic surgery.

THE STATE OF GENDER REASSIGNMENT SURGERY

While his transgender work has improved his aging-face results, Spiegel says more work is needed to improve upon the surgical options for transgender patients.

“Male-to-female facial feminization surgery is very complex and necessary to help people make the transition,” he says. Facial feminization surgery procedures may include procedures that many facial plastic surgeons are comfortable with, such as rhytidectomy, brow lift, cheek implantation, and lip augmentation, as well as the less familiar scalp advancement, frontal cranioplasty, lip lift, and reduction mandibuloplasty. Also, some familiar techniques, such as rhinoplasty, require a very different approach when doing gender-confirming surgery.

“It’s a challenge for transgendered women that facial feminization surgery is very complex and not many surgeons have the experience to get excellent results, but on the plus side, the genital reassignment is very well done,” he says. In addition, if you take feminizing hormones, breasts develop and there will be some hair growth and fat distribution changes that can help an individual to look more feminine.

In female to male surgery, “The facial aspect is less complicated because hormone therapy is typically enough to allow you to be perceived as a man,” he says. But “The genital reassignment surgery is very inadequate. It is difficult to create a reasonable phallus that will either look right or function correctly.”

INTERNET REMOVES BARRIERS, FUELS AWARENESS

A key to allowing transgendered individuals to get the help they need has been the Internet. “Twenty years ago, you imagine a young person who has these feelings that they are presenting as the wrong gender, but there was no one to talk to or learn about it,” he says.

The Internet has removed these silos, and allowed transgender individuals to find one another, skilled professionals, and ultimately their true self through psychological counseling and medical interventions. “There is community and a way to learn about what’s happening and find appropriate resources,” he says.

This is the path that led Boston-based techie Lida, 59, to Spiegel. She was born in 1954, 2 years after Christine Jorgensen became the first widely known person to have sex reassignment surgery, but the topic was still übertaboo, and as a result Lida and many others like her hid their true selves from everyone—including themselves.

“I was almost done with high school when I figured out how to act so I would not get picked on, and then the act continued. I didn’t even realize I was doing it anymore,” she says.

Lida met with Spiegel at a transgender medical conference. “One of the things that I liked about him, aside from his personality and sense of humor, is that his philosophy is ‘less is more,’?” she says. “When it was all done, I wanted to still look like my mother’s daughter.”

But there is another, possibly more important, factor that led her to Spiegel—his compassion. Treating transgender patients surgically involves a particular technical skill set and an aesthetic eye, but there is more to it. Sensitivity should be second nature for health care professionals, but often it isn’t. “When I had my lower face lift, there was a nurse that kept using the wrong pronouns,” Lida recalls. “Dr Spiegel took her in the hallway and said, ‘That is a woman, and you need to treat and address her as one.’?”

Lida had bottom surgery and breast augmentation roughly 1 year after facial feminization surgery. Everything was covered by her employer—except for a chin implant, which she admits was largely just to correct a pet peeve. “I am legally and functionally female and couldn’t be happier,” she says.

“My patients are extraordinary courageous people who identified a disquiet within them, explored it, and made a very difficult decision to seek wholeness and wellness,” says Spiegel with awe.

Original citation for this article: Mann, D. Gender bender, Plastic Surgery Practice. 2013; Winter: 12-17