|

Sooner or later, nearly all of the women who have acquired breast implants will need to visit the surgeon again.

Although breast augmentation is one of the fastest-growing surgical procedures in the world—with nearly a 60% increase in United States-based procedures since 2000 to more than 330,000 annually—a majority of the patients will require at least one reoperation over the course of their lives.

Data submitted to the FDA by breast implant manufacturers Allergan Inc and Mentor Corp recorded surprisingly high reoperation rates within the first 5 years of implantation after primary breast augmentation.

Capsular contracture and size-change procedures are implicated in many of these breast-revision procedures.

It has become clear from the work of John B Tebbets, MD, and others that when sound biodimensional analysis, careful implant handling, and meticulous surgical technique are employed, we can significantly reduce the need for frequent early reoperations.

However, despite technical advancements and a steady improvement in implant design, many women will predictably present for revision and redo surgery.

By analyzing and understanding patients’ tissue characteristics, as well as the environment existing from previous breast implantation procedures, one can develop sound strategies for reoperative surgery.

THE AGING PROCESS

|

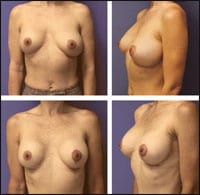

| Figure 1. This 35-year-old patient is shown before and 2 months after revision breast-augmentation surgery. She underwent two-stage implant removals, inferior capsulorrhapies, and submuscular reaugmentations with 450-mL implants. |

In addition to the changes that are produced from the interaction of the implant with the breast parenchyma, the breast tissue and skin envelope continue to exhibit age-related changes.

Frequently, the implant-parenchyma interaction has a tendency to induce thinning of the overlying skin and breast tissues.

The use of larger and higher-profile implants is more prone to accelerating these changes in primary augmentation and should be used selectively.

Paralleling the normal tendency of adult females to progressively gain weight from adolescence to the postmenopausal period, the fatty component of breast volume can increase significantly over time.

This can produce the scenario of women who were augmented in their 20s and then present overly large breasts 10 to 20 years later, seeking revision surgery.

Such changes are outside of the surgeon’s control. Treatment usually involves explanation and mastopexy with or without a smaller implant, depending upon the patient’s expectations of upper pole fullness.

Progressive breast ptosis will clinically occur in the augmented breast in the absence of capsular contracture. When presented with these changes, many patients will come to discuss revision surgery involving implant replacement with larger devices or mastopexy-augmentation surgery.

Patients who present with minimal ptosis, soft breast pockets, and good tissue quality—and who object to potential mastopexy procedures—may achieve satisfactory results by simply upsizing implants by 15% to 20%, as well as being willing to tolerate minor capsular scoring.

In preoperative discussions with patients, you should explain that the nipple position might remain slightly ptotic relative to the implant, absent a mastopexy procedure.

|

| Figure 2. This 38-year-old patient had bilateral capsulotomies, left capsulorrhaphy, reaugmentation with the same implants, and a left mastopexy. She is shown before and 2 months after her procedures. |

Attempts to correct more significant ptosis with larger implants and inframammary fold lowering frequently lead to rapid recurrence of the ptotic condition and predisposes the patient to inferior implant malposition.

Mastopexy after a previous breast augmentation is also more prone to complications. However, it can be performed successfully when less parenchymal division and tension on the closure are employed.

The Velcro-like adherence that textured implants can promote can be advantageous for maintaining implant position in this type of surgery, but will demand a virgin peri-prosthetic pocket for maximum effectiveness.

Consideration of either staged surgery or the downsizing of the implant volume can be a prudent maneuver in these operations, particularly in the face of prior subglandular augmentation.

PECTORALIS-IMPLANT INTERACTION

Partial submuscular or “dual plane” implant coverage arose as a strategy to provide better upper-pole implant coverage. It was widely embraced as a way to reduce capsular contracture by surgeons in the 1980s.

The advantages of this technique must be weighed against the potential for implant displacement and distortion with pectoralis muscle contraction.

Analysis of this existing pectoralis-implant interface is important in planning revisional breast surgery.

Depending upon the degree of pectoral coverage, the implant may be gradually pushed inferior-laterally or remain somewhat high on the chest when more of the implant is submuscular, or when some unreleased inframammary pectoralis attachments remain.

Patients with large amounts of breast tissue also tend to gradually demonstrate ptosis of the breast over the muscle, with the implant remaining cephalad, producing the so-called “Snoopy deformity.”

Mild secondary ptosis occurring over a subpectoral implant may be correctable with the replacement of the larger implant to the subglandular or subfascial plane.

Maintaining the implant subpectorally will likely necessitate a mastopexy procedure and capsular revision of some sort.

When planning these mastopexy operations, you must take into consideration that an inferior-based glandular pedicle is not a reliable option in the face of prior inframammary incisions.

CAPSULAR ISSUES

Encapsulation of an implant is a normal foreign body reaction. It can provide stability of the periprosthetic space, but it frequently leads to outcomes that are one of the leading causes of reoperation.

Capsular contracture is a pathologic process that has been attributed to many etiologies, including infection, hematoma, implant rupture, and silicone-gel bleed.

Revisional surgery for high-grade capsular contracture will usually require total or near-total capsulectomy.

Alternatives to capsulectomy include a site change over or under the pectoralis major or conversion to the evolving concept of neo-subpectoral pocket site change, as have been described by Spear.

A number of methods have been prescribed for reducing and treating established capsular contracture. In addition, it is difficult to make sense of the literature.

Many practitioners agree that minimal handling of the implant, combined with antibacterial solution preparation, clearly affect early capsule formation.

Information on surface texturing and submuscular placement has suggested contradictory results, but these results are generally thought to be associated with fewer high-grade capsules.

Polyurethane-covered devices were effective in reducing capsular contracture recurrence, but these products are no longer available in the American market.

Highly cohesive, fifth-generation silicone implants from Allergan and Mentor have produced dramatically lower capsule rates in early reports, compared with traditional silicone gel implants.

Deliberately creating oversized implant pockets to maintain softness was an idea that proliferated during the emergence of smooth, round breast implants. Ultimately, though, this leaves many patients with progressive deformities over time.

Manipulation of existing capsules is one of the most potent maneuvers available to surgeons to correct this type of implant malposition.

The concepts of synergistic capsulorraphy and capsulotomy have allowed significant control of the periprosthetic space, particularly in implants that are inferiorly or laterally displaced.

In patients with thinner capsules, bilayered capsular flaps can be fashioned to reinforced capsulorraphies.

|

| Figure 3. This 40-year-old patient is shown before and 3 months after surgery. She had anterior capsulectomies, subpectoral reaugmentations with 380-mL implants, and bilateral mastopexies. |

The use of animal- or human-sourced biologic implants to control implant position has an established track record in reconstructive surgery and has been adopted by some in reoperative aesthetic cases.

The significant expense of these products is a practical barrier to their wider use.

EXISTING IMPLANT CHARACTERISTICS

Silicone gel implants that had been classified as second or third generation, and which were manufactured in the 1970s and 1980s, produced many of the complications that led to the FDA’s decision to ban the devices.

These implants were characterized by having thin shells with low-viscosity gel that produced high rates of gel bleed and early implant rupture.

These devices were also prone to thick capsule formation even when intact, due to gel bleed. Reoperations on implants of this era should assume rupture. Both patient and physician should prepare for a necessary but potentially difficult total capsulectomy.

Polyurethane-covered silicone implants, once widely used but no longer available in the United States, have been noted to produce an unusual late delamination phenomena in vivo.

This results in a densely adherent implant-capsule interface that is difficult to dissect.

Experience with these polyurethane implants suggests that a planned total capsulectomy may be the most effective procedure for reoperation in these patients.

Saline implants emerged as the predominant product in the United States following the FDA’s 1992 moratorium on the sale of silicone devices.

|

See also “The Innovator,” by Rich Smith, in the October 2007 issue of PSP. |

The saline-filled devices may be more prone to inferior malposition and bottoming out from a “piston-like” tissue-expansion effect of the fluid on the lower pole from gravity.

Whereas high-grade capsules are seen with saline implants, most patients tend to present with thinner capsules than what is found in silicone gel devices.

This characteristic can leave flimsier substance available for revisions involving standard suture capsulorraphy, and may require complex imbricated capsular flaps, pectoralis slings, or prosthetic material to control implant position.

Robert Oliver, Jr, MD, completed his general and plastic surgery training at the University of Louisville, Ky. Oliver’s clinical interests include aesthetic plastic surgery, emerging technologies, and breast reconstruction after cancer operations. Double board certified by both the American Board of Surgery and The American Board of Plastic Surgery, he can be reached at .