Breast surgery is a challenging passion. For those of us who love breast surgery, the challenge remains to safely obtain an aesthetically pleasing breast with which the patient is satisfied, while considering the limitations of individual anatomy, vascularity, and balancing patient expectations.

Each and every case is different in some regard. The best weapon against poor results is sound surgical judgment coupled with extensive preoperative counseling and communication with the patient, so that there are no postoperative surprises or unrealistic expectations.

When I first began my private practice, I was excited to start seeing new patient consults. I thought that I would start out with some simple, straightforward cases and slowly graduate to more complex, challenging cases. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case. I seemed to be thrust into the mix—a “baptism by fire,” so to speak.

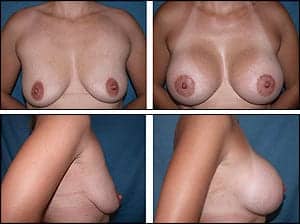

Figure 1. A thin, young female with previous saline implants, severe capsular contractures, and asymmetry. She desired correction and much larger implants.

My very first breast consultation was a tall, young, extremely thin, and attractive female who weighed about 95 pounds soaking wet. She had saline implants placed previously in the subglandular plane and presented with severe Grade IV capsular contractures, wide cleavage, glandular ptosis, and dissatisfaction. I don’t know which one of us was more horrified by her outcome. In addition, she was extremely influenced by her Southern California girlfriends, all of whom had “really big boobs,” a designation she truly coveted, and she desired to be at least a DD bra cup size (or larger).

We discussed the complexity of her breast issues in great detail. I emphasized how the size of replacement implants would be dictated by her anatomy, and how she had such a narrow chest diameter and thin body habitus, that I was limited as to the size of implants I could place safely. Some might think that she had a psychological disorder, but after examining her breasts I was surprised by how long she had lived with such a horrible result and severe deformities. I felt absolutely compelled to help her. I don’t know if I was naïve, noble, or just plain stupid. I truly felt that I could improve her significantly. I had received extensive training and experience with complex breast surgery during my residency and cosmetic fellowship. Why couldn’t I help her?

She underwent removal of old saline implants, capsulotomies, and placement of larger, 550-cc silicone Implants in the partial submuscular plane with vertical mastopexies.

I soon realized that the reason this consult was referred to me was that nobody else wanted to take on this case. But I persisted anyway. My surgical plan was to remove the old saline implants, perform capsulectomies, then put in replacement silicone implants in the partial sub-muscular plane and perform bilateral mastopexies.

We had discussed all the potential complications of this revisional surgery preoperatively, including but not limited to VTE, PE, infection, hematoma, seroma, nipple necrosis, poor scarring, wound-healing problems, numbness, implant exposure, recurrent capsular contracture, recurrent ptosis, smaller implants than what the patient desired, asymmetry, and an overall poor cosmetic result.

I placed 550-cc silicone gel implants in the partial submuscular position and performed vertical mastopexies with a decent result—and fortunately with no postoperative complications (Figure 1). Her only complaint was that I “didn’t make her big enough.” At first, I was disappointed. I later realized how very lucky we were that this was her only complaint and nothing disastrous happened.

As we mature as plastic surgeons, we all become more experienced, more knowledgeable, conservative, and rightfully cautious. Presently, the words of Scott L. Spears, MD, and Mark Gorney, MD, FACS, constantly ring in my ears: “Surgeon beware.” I remain grateful that my patient ultimately had a good result, but I am also much more conservative regarding my approach to complicated breast revision surgery.

GENERAL APPROACH TO PROCEDURES

Figure 2. A 25-year-old tall, thin mother of two children who complained of “deflation and sagginess” of her breasts after breastfeeding and wanted a much larger, fuller “D”-cup breast size. She had asymmetry of her breasts and nipple-areolar complexes. Thus, upper peri-areolar incisions were used in order to perform a right crescent mastopexy for improved symmetry. Smooth, round, 500-cc high-profile silicone implants were placed in the partial submuscular plane.

General preoperative workup includes a current mammogram, documentation of any implant rupture, documentation of capsular contracture if this exists, documentation of preop nipple sensitivity, proper photographs, cessation of any herbals or blood-thinning medications, cessation of estrogen, smoking cessation, and proper medical clearance.

Primary breast augmentation is a relatively straightforward procedure for the experienced cosmetic surgeon. Presently, I offer the patient either a peri-areolar or inframammary approach. If the patient has mild to moderate asymmetry, I utilize an upper, peri-areolar incision so that a crescent mastopexy can be performed without creating an additional scar (Figure 2). If the patient requires areola reduction, then a circumareolar incision is utilized.

The operation becomes more complicated when the patient has breast ptosis and asymmetry. Sometimes, it is difficult for patients to accept that they require mastopexies to improve their breast shape and symmetry. You must explain that they are trading a scar for improved shape.

Some are willing to accept the scars, and others are not. I make it a point to show photographs of breast scars at various stages of healing. Some of the most difficult patients are young girls who sought breast augmentation with another surgeon due to bargain pricing, and have very large implants placed in the subglandular pocket. These women often complain that they had “small, saggy boobs” preop, and now they have “big, saggy boobs” and desire correction. They are often dismayed to learn that the “fix” is far more complex than if they had the original operation performed correctly. Furthermore, these young women often do not have the financial resources to pay further toward a revision that will often cost more than their original surgery. They often state that they told their original surgeon that they thought they needed a lift, but that the surgeon either didn’t counsel them on this, felt they didn’t need lifting, and/or didn’t perform mastopexy.

Left breast reduction (intraop “Dermal Bra-Flap”). Patient had approximately 8 pounds of breast tissue removed.

Figure 3. Preop markings for a large breast reduction.

Also, in order to fill out the breast envelope with significant ptosis, very large implants have typically been placed. It is a difficult situation with no easy solution. These women often need to wait further until they save up the money to have a proper revision performed, or just live with their unsatisfactory results.

This situation exemplifies the importance of preoperative counseling. You should warn patients of the potential poor outcomes that can occur if they do not undergo the proper procedure for their anatomy and desires. In addition, I am surprised by how many young women state that they were never counseled regarding capsular contracture. This is amazing to me since capsular contracture is so common and remains our major nemesis in regards to breast implant surgery.

I make it a point to emphasize the possibility and rates of capsular contracture, and also how it may be recurrent and remains unpredictable. I have not yet adopted any prophylactic routine since there are no definitive scientific studies regarding this; but I am well aware of the usage of certain leukotriene receptor antagonists for both prophylaxis and treatment of capsular contractures.

I reserve the usage of Singulair 10 mg po Q Day for early capsular contracture with the realization that it may not be effective at this stage. However, I counsel patients regarding the potential side effects, including hepatotoxicity of these types of medications and the reasons why I do not routinely prescribe them. I will have patients start Vitamin E supplementation and gentle massage postoperatively once they are no longer tender.

During my aesthetic fellowship, I had the great opportunity to research and publish regarding the safety and efficacy of combined breast augmentation with mastopexy. This is a fascinating topic and one of my favorite operative challenges.

I realize that many surgeons stage the two operations, and there are certain cases where staging of the operations is indicated and desirable. Usually, women state that they wish to have the surgery performed in a single stage if possible, to minimize both anesthesia and recovery time.

NO SMOKING, PLEASE

I will not perform the operation on active smokers. I counsel them on the dire consequences of smoking on wound healing and infection rates, and severe complications including vascularity issues and potential nipple necrosis. My current policy is to have all breast surgery patients quit smoking for at least 1 month prior to surgery and 1 month afterward. (Longer is always preferable but sometimes not practical.)

Breast reduction preop. 1 week postop. 6 months postop.

Breast reduction preop. 1 week postop. 6 months postop.

I used to perform a serum nicotine test preoperatively. The only problem with this test is that it may take a couple of weeks for the results to come back. Therefore, I have now adopted performing a urine cotinine dipstick test on the morning of surgery to ensure that patients are smoke-free, something that I learned from the great patient-safety courses by V. Leroy Young, MD, FACS, and Felmont Eaves, MD.

If the nicotine test is positive, the surgery is cancelled. All of my patients are made well aware of my reasoning. Also, all patients with even a remote history of smoking must read and sign the ASPS “Smoking & Plastic Surgery” form during the preop visit, to ensure that all the risks of smoking as related to plastic surgery have been explained, outlined, emphasized, and understood. Also, they must check all the areas in the informed consent form regarding the fact that they were a smoker.

Even patients who quit smoking can still have microvascular abnormalities and wound-healing problems. I emphasize how disastrous this can be, particularly in light of the fact that prosthesis is involved. Patients seem to accept and appreciate this warning and conservatism. You may lose the occasional patient who has trouble quitting smoking. However, patient safety and best outcomes are the ultimate goal and certainly more than worth the risk.

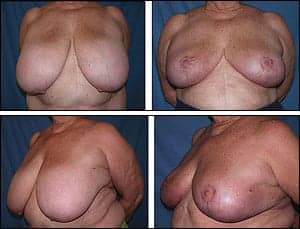

Figure 4. A 35-year-old female who had large saline breast implants placed above the muscle by another surgeon. The patient developed severe, grade IV capsular contractures of both breasts, asymmetry, and extreme dissatisfaction. She underwent correction, with removal of the old saline implants, capsulectomies, replacement with 500-cc silicone implants under the muscle, and correction of her stretched-out areolar size and shape with bilateral “inverted-T” mastopexies in a single surgery.

One of the most difficult types of breast revision cases that present is the patient with old, usually ruptured implants typically placed in the subglandular position, with capsular contractures, a stretched-out breast envelope with widened areolas, and severe ptosis.

In my practice, I have encountered yet another patient population that adds to the complexity of this presentation—and that is the more senior patient who is typically older than 60 years with thinner senescent skin and slower overall healing capability.

Surprisingly, I have found these mature women to often be very fit, healthy, and active. They are also quite motivated and determined to have their breasts revised in order to look good in their swimsuits, country-club wear, expensive clothing, and evening gowns for when they attend their multiple charity and social events. If the women are healthy and have preop medical clearance and realistic expectations, I am not averse to performing their operations.

I always warn that the postoperative recovery is not a “walk in the park” and that their recovery may be difficult, painful, and prolonged so that they have a complete understanding of the complexity of the operation, and that they will likely not recover as quickly as they are used to when they were younger. Most women understand and do surprisingly well.

OPERATIVE APPROACH TO COMPLEX BREAST REVISIONS

Preop Markings

With the patient in a sitting position in the preop area, I mark the following areas: clavicles, sternal notch, midline, inframammary folds, breast meridians, areola outlines, upper breast borders with the breast tissue elevated, and areas of thickening due to capsular contracture. In addition, I estimated new nipple position, as determined by finger palpation outward from the mid-inframammary fold.

I make vertical and horizontal lines starting from the nipples and draw them outward along and past each areola at the 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock positions, for orientation. I measure the sternal notch to nipple distances, the nipple to inframammary fold distances, the breast base diameters, and areola diameters. I estimate how far the nipple will need to be elevated to its new position.

Intraop Markings

I perform these with the patient lying supine on the OR table with arms outstretched, padded, and secured after induction of anesthesia. I place staples around the nipple at the 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock positions for orientation. Staples are placed at the midpoint of each inframammary fold and in the midline. I find that staples are better since pen marks often smudge and are sometimes inadvertently erased.

Next, the breast is held in a very gently stretched position and the new areola outline is made typically with a 42-mm areola marker (or freehand, if necessary). If the patient has small areolas, then her native areola is outlined and kept the same size. The remaining mastopexy markings are made later, using a “tailor-tacking” technique with the patient in the upright position.

Operative Technique

Approach to the breast is made via a vertical incision along the midlower pole, as this is the area where the vertical component of the mastopexy scar will lie. The implant is removed, inspected, and photographed; and capsulectomy is performed. A subpectoral pocket is created. The pocket is irrigated with triple antibiotic solution as described by Rohrich et al. A JP drain is placed within the pocket.

Marcaine with epinephrine is used to tumesce the pectoralis muscle and is also placed free within the pocket for postop analgesia. A no-touch technique with fresh, powder-free gloves is used to place the new breast implant. With saline implants, I use a closed-system filling approach. However, the majority of my revisional patients choose silicone replacement implants.

The vertical breast incision is sutured and closed in layers. The mastopexy flaps are kept quite thick, and very minimal undermining is performed (in order to preserve vascularity). At times, a “skin-only”-type mastopexy is performed.

Next, the patient is sat upright and the mastopexy scar-design is created utilizing a “tailor-tacking” technique with staples. The staple outline is marked with a pen, and hatchmarks are made for proper reapproximation.

The patient is returned to supine. All staples are removed, and the excess skin is de-epithelialized sharply with the scalpel. The skin edges are reapproximated with staples. Then, all incisions are closed in layers with 0-Vicryl sutures deeply. Multiple 0- and 3-0 Vicryl buried, subdermal sutures are then placed.

Figure 5. This 70-year-old woman (who thought she was “too old” to undergo breast reduction surgery) had complete symptom relief and an uneventful recovery without complications.

The final skin closure is performed with running, Monocryl subcuticular sutures. The incisions are dressed with Bacitracin ointment, Xeroform gauzes, and dry dressings. The patient is then wrapped with Kerlix roll and large Ace wraps for compression for the first 24 hours, after which the surgical wrap is removed and the patient is placed in a surgical bra.

Breast Reduction

I find breast reduction patients to be some of the most happy and satisfied patients I treat. They are extremely grateful, and nearly all attain complete symptomatic pain relief as well as an improved appearance of their breasts.

Mainly, I utilize a medial pedicle for small-to-moderate reductions, and an inferior pedicle for large reductions. The majority of women who come to me regarding breast reduction surgery are typically very large with extreme macromastia. I have found the inferior pedicle technique to be safe and reliable in my hands.

The scar design varies. A vertical scar design is typically used for smaller reductions, a “J”-type or limited “anchor”-type scar design for moderate reductions, and a full inverted-T (“anchor”-type) scar design for large reductions.

Presently, I do not perform liposuction routinely during breast reduction surgery, and reserve liposuction to the “bra-fat” areas only if desired by the patient.

WARNING SIGNS

There are several factors that make me advise a patient against breast reduction surgery. The most serious is active smoking. I will not perform the procedure on patients who are active smokers for the reasons stated previously. I encourage smoking cessation and perform nicotine testing preoperatively.

Even patients who quit and/or have a history of previous smoking are still at risk, as I believe they have microvascular pathology that affects their skin perfusion and ultimately their wound healing. In my experience, the breast-reduction patients who have the highest incidence of postop wound-healing problems are those with a history of smoking.

Ruptured, old silicone implants and calcified capsules.

Figure 6. Preop markings.

The next group of patients at high risk are those who are obese with a BMI greater than 30. I encourage these patients to lose weight and get their BMI to less than 30 preoperatively. Unfortunately, many of these women generally have a much larger body habitus, as well as extreme difficulty exercising effectively due to the large size of their breasts.

Nearly all of my breast reduction patients have lost weight postoperatively, since their pain symptoms are alleviated and they are more mobile due to removal of the heavy breast tissue. Also, their large breasts act like a “metabolic parasite,” and once removed patients go on to lose weight effectively and more efficiently in other areas of their body with greater ease. This creates a positive cycle and helps to jump-start them onto a healthier lifestyle of exercise and ongoing weight loss. Therefore, elevated BMI is not a contraindication for me regarding breast reduction surgery. However, I do counsel them extensively on their elevated risks due to obesity so that they understand the seriousness preoperatively.

Any patient who requires lifelong anti-coagulation and cannot stop their medication safely during the perioperative period is also not a candidate for breast reduction surgery.

More red flags include patients who present with confusion regarding their expected results and/or have unrealistic expectations.

Any patient who is more concerned about cosmesis rather than symptom relief is not a proper candidate. The typical patient’s primary concern is removing breast tissue to achieve pain relief. The fact that her breasts will look better is a “bonus,” so to speak.

Also, I take care not to over-reduce breasts. These patients can achieve significant tissue removal and symptom relief, yet still maintain pretty and perky breasts that are proportionate to their typically larger overall body habitus. Also, as they lose weight postoperatively, they will continue to lose additional volume in their breasts.

Any patient who has had radiation therapy to their breast(s) is also at very high risk for wound-healing problems and unsatisfactory results. However, these patients often accept this risk in order to achieve pain relief.

Advanced age is no longer a contraindication for me to perform breast reduction surgery, so long as the patient is healthy enough to undergo the operation and medically cleared preoperatively. (Figure 6)

MOST CHALLENGING CASE

A 64-year-old healthy female with 26-year-old ruptured subglandular silicone implants, Grade IV capsular contractures, and ptosis. She desired replacement implants and full correction. Left: preop and (right) 1-year postop.

She underwent removal of old, ruptured silicone implants, capsulectomies, and partial submuscular replacement with 450-cc silicone implants and bilateral “inverted-T” mastopexies. Preop (left) and 1-year postop (right).

This woman had previous breast reduction performed in another country many years prior, and no operative records were available for review. Thus, I had no idea as to what type of pedicle was used during her initial surgery. I realize that there is some debate regarding the amount of time required for the breast to revascularize enough to allow for safe secondary breast reduction. However, I did encounter some nipple-areolar venous congestion and wound-healing difficulties on her larger side. Thus, I feel that more investigation is required to determine the length of time necessary prior to performing a secondary breast reduction more safely and reliably.

The majority of my patients have severe macromastia with sternal-notch to nipple distances greater than 30 cm. My most challenging breast reduction patient had very large breasts with a sternal-notch-to-nipple distance greater than 42 cm, hypertension, obesity, and was a smoker. She quit smoking 1 month prior to her operation.

I emphasized the extremely high-risk nature of her surgery. She was more than willing to accept the risks. I performed an inferior pedicle technique. During the operation, I noted that her lateral breast skin-soft-tissue flap was so long that it could reach her sternum. Thus, rather than excising this tissue, I utilized it and performed my first “lateral dermal bra-flap,” where I de-epithelialized the skin and swung the flap over medially to serve as an internal bra for improved support of the pedicle. I sutured the flap to the periosteum of the lower sternum and nearby ribs. Nearly 8 pounds of breast tissue was removed. (Figure 3)

What were the advantages to this technique? Obvious improved support of the inferior pedicle that provided better projection and less weight on the incisions durig the healing process. The major disadvantage was the increased operative time required to perform bilateral flaps.

However, in the end, the postop results were very good and the patient surprisingly had no wound-healing problems or complications despite her smoking history, comorbidities, and obesity. She remains one of my most grateful and satisfied patients to date.

CONCLUSION

Breast surgery is constantly evolving, and novel techniques are described annually. Those dedicated to breast surgery must consistently review and critique their surgical techniques and outcomes in order to strive to improve. The most exciting aspect of this field is that we are forever learning. New techniques and technologies keep evolving, and we must remain driven to perfect our skills in order to provide the best results possible for our patients.

Suzanne M. Quardt, MD, is chief of plastic surgery at Eisenhower Medical Center in Rancho Mirage, Calif. She can be reached at .

FURTHER READING

- Stevens WG, Freeman ME, Stoker DA, Quardt SM, Cohen R, Hirsch EM. One-stage mastopexy with breast augmentation: a review of 321 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(6):1674-1679.

- Stevens WG, Stoker DA, Freeman ME, Quardt SM, Hirsch EM. Mastopexy revisited: A review of 150 consecutive cases for complication and revision rates. Aesth Surg J. 2007;27(2):150-154.

- Stevens WG, Stoker DA, Freeman ME, Quardt SM, Hirsch EM, Cohen R. Is one stage breast augmentation with mastopexy safe and effective? A review of 186 primary cases. Aesth Surg J. 2006;26(6):674-681.

- Spear SL, Boehmler JH 4th, Clemens MW. Augmentation/mastopexy: a 3-year review of a single surgeon’s practice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(7 Suppl):136S-147S;discussion 148S-149S, 150S-151S.

- Spear SL. Augmentation/mastopexy: “surgeon, beware.” Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(7 Suppl):133S-134S;discussion 135S.

- Gorney M, Maxwell PG, Spear SL. Augmentation mastopexy. Aesthet Surg J. 2005;25(3):275-284.

- Spear SL, Pelletiere CV, Menon N. One-stage augmentation combined with mastopexy: aesthetic results and patient satisfaction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28(5):259-67. Epub 2004 Nov 5.

- Spear S. Augmentation/Mastopexy: “Surgeon, Beware.” Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(3):905-906.

TALKING POINTS

Quardt’s surgical approach to complex breast revisions is as follows:

Preoperative workup:

- Current mammogram

- Preoperative documentation of implant positioning and any implant rupture

- Medical clearance and labs

- Smoking cessation

- Cessation of all estrogen-containing medications

- Cessation of all blood-thinning medications, including over-the-counter medications, fat-burners, and herbal supplements

- Preop documentation of nipple sensitivity

- Preop breast measurements

- Preop photos

- Informed consent